by Gwyn Conaway

It seems to me there is a silent war going on in Vogue New York this month, perhaps a reflection in fashion of the recently heightened conflict between East and West. Read on with me — do you see it too?

Vogue; New York; Nov 1, 1962; Vol. 140 (8)

I turned the pages of November’s first issue over the weekend. The usual suspects filled the pages: Tiffany & Co., Bergdorf Goodman Co., Master Furriers Guild, Miss Clairol, among others. The Shop Hound features were more of the same from late summer: long-stemmed wine flutes, latticed jewelry, needlepoint purses, and silverware inspired by Futurism. But as I lazily perused the corselette and perfume advertisements, my boredom gave way to an intriguing discovery.

It seems fashion has split itself into two distinct personalities this season.

On the one hand, luxury brands are pushing women into futuristic, slim mod designs. We have seen this trend over the past several months. Both Christian Dior and Cisa have adopted the trend in knitwear and woolens.

“The world’s finest knitted fashions for the world’s smartest women.” Cisa.

Vogue goes so far as to feature an article called “All Day Any Day: The Plucky Little Wools.” This article not only promotes a modern aesthetic; the descriptions constantly return to the versatility of the garments in shape, style, and color. White, blue, red, beige, and lime-green are mentioned as an extremely flexible palette, suitable for day, night, and the country. Lacking collars and adornment in general, these fashions transform “ease” into a hallmark of luxury.

Smooth silhouettes and solid textiles are the hallmark of our season with an unshakable Mondrian-esque quality.

Naturally, this extreme departure from the past decade has left a longing for the exact opposite in its wake. Juxtaposed with the modern, I find a stroke of romanticism for the past in the issue. A piece on Mainbocher, the American couturier, identifies his timeless aesthetic. His grand, sweeping gestures with fabric harken back to previous eras of pique feminine beauty. In the face of our fast-paced world, women such as Miss Anita Loos and Mrs. Murray Vanderbilt return to these garments time and again.

Mainbocher’s drape and style take us back in time to the French Rococo.

Hoods and nightdresses are also being designed to portray mystic beauty. Seen below, a floral peignoir hides the intentions of the wearer in a delicate pool of florals around the face. Opposite, a sheer nightdress, pleated and inspired by the Greek muses. Perhaps even more interesting about this spread is the title of the article: “New Ideas for Clothes that Never Go Anywhere,” which suggests that mystic beauty is found in the private lives of modern women rather than in our public personas.

Warner-Laros; Bergdorf Goodman

Vogue’s pages suggest that while our public selves are geometric, structured, and convenient, our private selves long for delicacy and grace. Is this the magazine’s intention? I see this split personality all across its advertisements and articles: women dressed in contrasting colors and patterns, paired like twins. Are we truly this dichotomous?

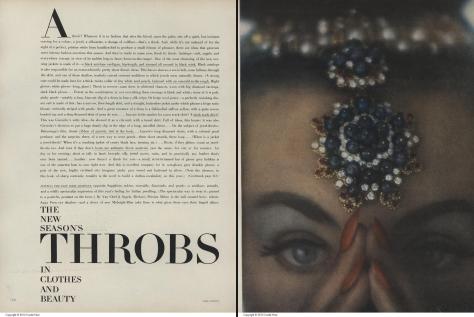

I found the final puzzle piece to this intrigue on page 110. The East India Company’s jewels create the perfect complement to the modern wools and knits of Christian Dior, Cisa, and others. India’s spectacularly detailed, opulent jewelry culture balances the modern aesthetic in a fresh and fulfilling way.

The New Season’s Throbs in Clothes and Beauty

And so the conflict runs full course and resolves itself. Perhaps we’re not splitting ourselves in two, but simply trying to find the perfect balance of extremes, in clothing and in the world. Only time will tell…