by Gideon Marcus

Science fiction has risen from its much maligned, pulpish roots to general recognition and even acclaim. Names like Heinlein, MacLean, Anderson, Asimov, and St. Clair are now commonly known. They are the vanguard of the several hundred men and women actively writing in our genre.

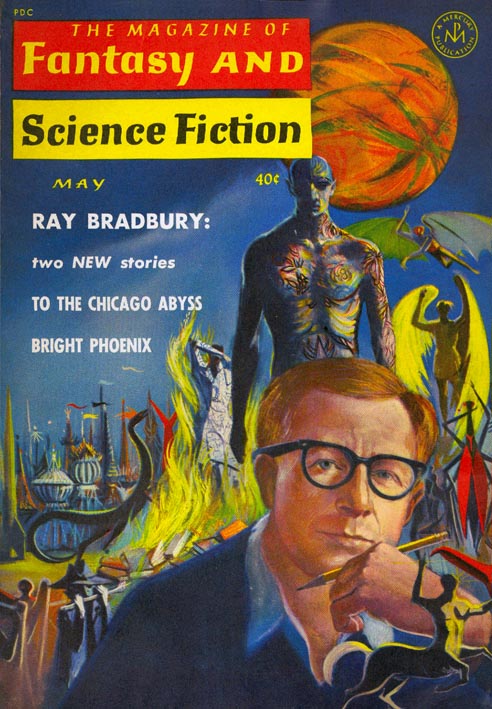

One name that comes up again and again on the lips of the non-SF fan, when you query them about the SF they have read, is Ray Bradbury. Thoroughly raised in and part of the "Golden Age" of science fiction, he has remained as he always was — a writer of fantastic tales. And yet, he's popular with the masses, and the reputation of our genre is greater for it. Thus, it's no surprise that Bradbury was chosen to have this month's F&SF devoted to him.

That said, I don't like Bradbury. Or, at least, I don't like what he writes.

Maybe it's because he insists that he doesn't write science fiction, which is true. His stuff has the trappings of SF, but it follows none of the rules of science. That kind of scientific laziness always bugs me. The only person I feel who can get away with enjoying the benefits of our genre while dislaiming association is Harlan Ellison, whose writing really is that good.

Or maybe it's because, as Kingsley Amis put it (and as William F. Nolan quotes in his mini-biography included in this issue), Bradbury writes with "that particular kind of sub-whimsical, would-be poetical badness that goes straight to the heart of the Sunday reviewer." I've never read a Bradbury story that I didn't think could have been better rendered by, say, Ted Sturgeon.

Or maybe it's just sour grapes. After all, Bradbury is two years younger than me and much more famous. Heck, I've barely gotten to the point of accomplishment he was at twenty-three years ago! On the other hand, I don't feel that resentment for, say, Asimov (another lettered colleague of similar age).

Anyway, I suspected an issue about Bradbury would be a bad one, and in fact, it's not a great one. Still, there is stuff worth reading. And if you're a fan of Ray's, well, this will be a treat:

Bradbury: Prose Poet in the Age of Space, William F. Nolan

Bradbury's Boswell is a minor SF writer, fairly recent to the scene. Nolan became pals with Ray in his fandom days in the early '50s, and he is sufficiently versed with Bradbury's career to write a perfectly fine biography. Worth reading. Four stars.

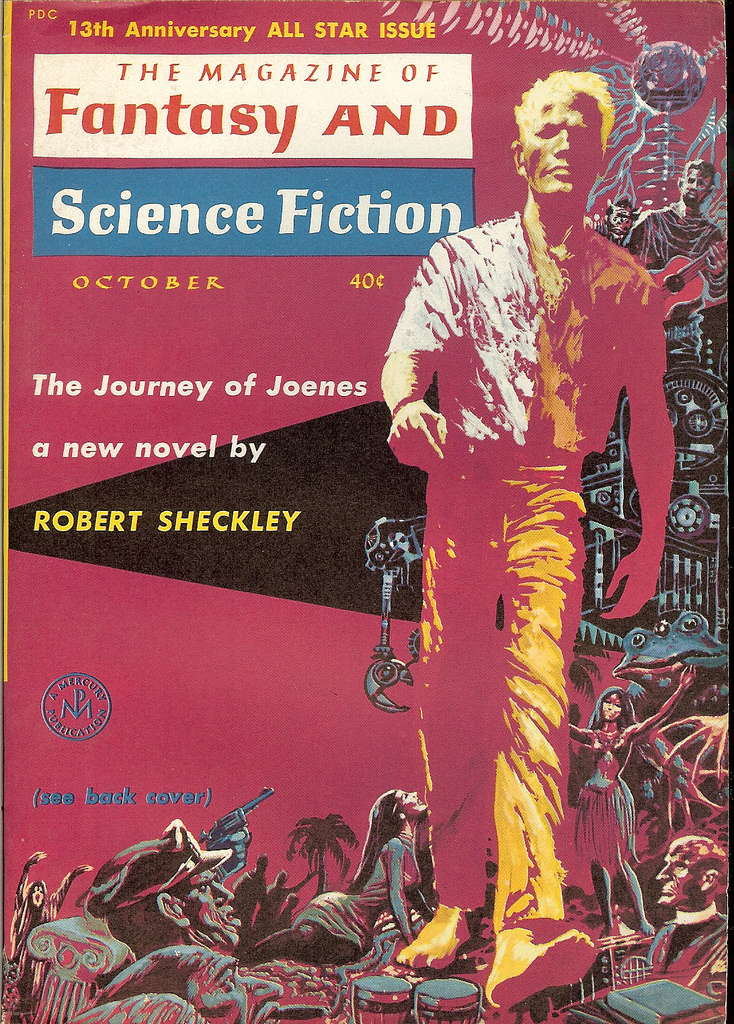

Bright Phoenix, by Ray Bradbury

F&SF editor Davidson has apparently persuaded Ray to part with a couple of pieces of "desk fiction" — stuff that didn't sell, but which now has value since the author is famous. Phoenix is the original version of The Fireman, set at the beginning of the government campaign to burn seditious (i.e. all) books. The Grand Censor's efforts are thwarted by the grassroots project whereby library patrons take it upon themselves to memorize the contents of the books, thus preserving the knowledge.

It's a mawkish, overdone story, but at the same time, it accomplishes in less than ten pages what it took Bradbury more than a hundred to do in his later book. Had I not known of The Fireman, and had I read this in 1948 (when it was originally written), I might well have given it four stars. As it is, it's redundant and a bit smug. Three stars.

To the Chicago Abyss, Ray Bradbury

This longer piece is a variation on the same theme. An old man, one of the few who remembers a pre-apocalyptic past, continually runs afoul of the authorities by recounting fond memories to those who would vicariously remember a better yesterday. It's another story that pretends to mean more than it says, but doesn't. Three stars.

An Index to Works of Ray Bradbury, William F. Nolan

As it says on the tin — an impressive litany of Bradbury's 200+ works of fiction. Look on his works, ye Mighty, and despair.

Mrs. Pigafetta Swims Well, Reginald Bretnor

From the writers of the increasingly desperate Ferdinand Feghoot puns comes an amusing tale of an opera-singer bewitched by a jealous Mediterranean mermaid. Told in a charming Italian accent, it is an inoffensive trifle. Three stars.

Newton Said, Jack Thomas Leahy

New authors are the vigor and the bane of our genre. We need them to carry on the legacy and to keep things fresh. At the same time, one never knows if they'll be any good, and first stories are often the worst stories (with the notable exception of Daniel Keyes' superlative Flowers for Algernon).

So it is with Jack Thomas Leahy's meandering piece, built on affected whimsy and not much else, of the face-off between a doddering transmogrifying elf and his alchemically inclined son. One star.

Underfollow, John Jakes

This one's even worse. A citizen of Earth, for a century under the thumb of alien conquerors, decides he's tired of the bad portrayal of humans on alien-produced television shows. He tries to do something about it. His attempts backfire. I read it twice, and I still don't get it. I didn't enjoy it either time. One star.

Atomic Reaction, Ron Webb

Deserves a razzberry as long as the poem. Two seconds should suffice. One star.

Now Wakes the Sea, J. G. Ballard

British author Ballard has a thing for the sea (viz. his recent, highly acclaimed The Drowned World). This particular story starts out well, with a man, every night, dreaming of an ever-encroaching sea that threatens to engulf his inland town. It's atmospheric and genuinely engaging, but the pay-off is disappointing. Colour in search of a plot. Three stars.

Watch the Bug-Eyed Monster, Don White

Don White has a taste for the satirical. Here, he takes on stories that start like, "Zlat was the best novaship pilot in the 81 galaxies," by starting his story with, "Zlat was the best novaship pilot in the 81 galaxies." The problem is, a satire needs to say something new, not just repeat the same badness. One star.

Treaty in Tartessos, Karen Anderson

Now things are getting better. In Ancient Greece, the age-old rivalry between humans and centaurs has reached an unsustainable point, and an innovative solution is required. A beautifully written metaphor for the conflict between the civilized and the pastoral whose only flaw is a gimmicky ending. Four stars.

Just Mooning Around, Isaac Asimov

The Good Doctor presents a most interesting piece on the tug of war over moons between the sun and its planets. The conclusion, in which the status of our "moon" is discussed, is an astonishing one. Five stars.

No Trading Voyage, Doris Pitkin Buck

A lovely piece on the troubled trampings of a dispossed starfaring race called humanity. Four stars.

Niña Sol, Felix Marti-Ibanez

The Brazilian author who so impressed me a few months back has returned with an even better tale. Writing in that poetic, slightly foreign style that one only gets from a perfectly fluent non-native speaker, Mr. Ibanez presents us a love story set in Peru between an artist and a Sun Elemental. Beautiful stuff. Maybe Bradbury should go to Rio for a few years. Four stars verging on five.

If you're a Bradbury fan, then the emotional and fantastic character of this month's issue will greatly appeal to you. And even if you're not, there's enough good stuff at the ends to justify the expenditure of 40 cents.