by Joe Reid

I'm a man who enjoys science fiction, having read his share of it. I am also a student of religious thought, having again also read a good amount. I did not start off reading the books of C.S. Lewis with the intent of seeking spiritual insights. After all, I received none on reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) as a child. Nor did I come to a better understanding of forgiveness in the pages of Prince Caspian (1951). I learned nothing of redemption from The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952). The Silver Chair (1953) did not strengthen my grasp on the doctrine of sanctification. Although the concepts were present on the page, my young heart only cared about the adventures in the wonderful land of Narnia. I loved all of the Chronicles of Narnia. It wasn’t until I read them again as a man, through mature eyes, that I bore witness to what lay beneath. On that second reading I was also no stranger to many of Lewis’ other works.

Lewis was an absolutely brilliant Christian philosopher. Some of his seminal works of religious thought include Mere Christianity (1952), The Problem of Pain (1940), and The Four Loves (1960). He is better known for his other works of fiction, which include The Screwtape Letters (1942), The Great Divorce (1945), and Till We Have Faces (1956). All of these beautifully penned volumes are rich treasures of wisdom, and I found them edifying to no end.

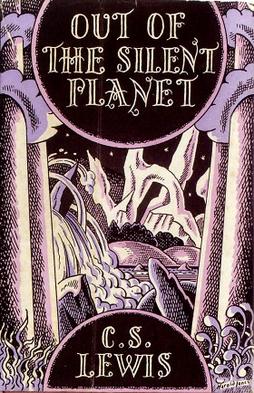

Clive Staples Lewis passed away a few short years ago in 1963. His death spurred me to revisit his works. It was then that I came across books of his that I was not at all familiar with: Three books of what appear to be science fiction from the hand of a writer that I grew to love and admire. The first of these works was released back in 1938. Suffice it to say, I was very enthusiastic to read the stories that have come to be known as the Space Trilogy.

As a man who enjoys science fiction, and who wrote such a glowing preface regarding my love for the works of C.S. Lewis, one would imagine that I also loved The Space Trilogy. The short answer is yes, I enjoyed reading these books. That said, I do not consider these books to be works of science fiction. Some discussion is required to figure out what they actually are, if not science fiction.

The first of the three novels, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), is the nearest that any of these books come to being SF. It follows Elwin Ransom, a philologist, who is abducted by two men, taken from Earth in their spacecraft to the planet Mars for an unknown purpose. (Philology is the study of the structure of language and literature.) What follows is a story rich in the descriptions of the world of Mars, or Malacandra as it is known to the native species, deep connections with the peoples of the world, and revelations as to the histories of Mars, Earth, mankind and Martian kind are laid out before us. For me, it was a pleasurable read.

Although there are elements of science in the story, the world and the inhabitants of the world might as well have been Narnian. Their stated motivations of familial love for some and ambition for others appeared to be the foundation for his later, more popular works. Also, no one in the book felt alien; fantastic, yes, but not alien. The Martians or Malacandrans, in the end, showed more humanity than any of the humans in the story.

If I were to place this book into a genre, I would call it fantasy/science fiction or science-fantasy for short.

In the second novel, Perelandra (1943), we visit Elwin Ransom again. He is a changed man living in a world changed by the events of the first novel. This time, Ransom is called to the adventure he embarks upon by a being he met in the last book, an adventure to Perelandra, the planet Venus, to help a woman on this young world from being corrupted.

The tone of this book starts off the same as the tone in the middle of the first book. The world is beautiful, yet different than Malacandra. Everything is fresh and exciting, until the introduction of one character that changes everything. It’s a story that felt enriching at first, but suddenly became disturbing. An object of relaxation which became a source of anxiety. An anxiety that one is not released from until near the end of Perelandra.

Perhaps Perelandra might qualify as science fiction? The answer again is no. This book forced me to stop reading for a time recover from the dread and terror that were a part of this story. I found myself frightened not only of the characters, but for them at the same time. Reaching the end of Perelandra and escaping with my life was the reward for completing the volume. It's an excellent book, but none of it is science fiction: there are no elements of the world or the characters that are forward looking or advanced. Even the method employed to travel to Venus was more ancient and magical than science.

The final book of the Space Trilogy is called, That Hideous Strength (1945). The entirety of this story is set on Earth (Thulcandra). We are introduced to new characters: a newly married couple named Mark and Jane Studdock, both well educated and ambitious young people. This story overall is cold and gray. Gone are the colors and wonders of the other worlds.

Earth is the way that it is because of events that were revealed in the other books. The tone of this story is very heavy and very dark, becoming heavier and darker with each turned page. The reader that perseveres is rewarded with a turn of fate so utterly unexpected and satisfying that one is left feeling well served by the story, even though some of what happened made absolutely no sense at all.

Again, this is not science fiction. The scientific elements in this story are so devoid of hope that the solution to the main dilemma of the book has to find its redemption from the fantastic. Neither is this story fantasy, nor terror.

This volume successfully avoids a genre and it is not until one takes all 3 novels together as a unified work that a genre can be laid to bear on the triptych.

In the same way that a mature reading of the Chronicles of Narnia as an adult reveals them to be at the core works of Christian philosophy to educate children, the Space Trilogy is a work of Christian philosophy to educate adults. The type of adult that enjoys science fiction.

These volumes are philosophy lectures cleverly wrapped in the garb of science fiction. This is not a criticism: I find them to be beautiful, terrible, revolting and inspiring. I love them for what they are regardless of what they pretend to be.

Another reader, who does not hold the same religious baggage that I carry, might find The Space Trilogy of C.S. Lewis boring at times and heavy handed at others. Unless one develops a desire to finish the stories, as I did, each book provides the user with many opportunities to exit and I assume that many do.

Again, I love the stories in the Space Trilogy, not necessarily because of what happened in them, but more because of how it made me feel and where it left me in relation to my faith when all was said and done. I would recommend this series to those who already love the works of C.S. Lewis and readers of science fiction who hold religious convictions. I would not recommend it to readers of science fiction that do not.

5 stars

![[May 22, 1967] Parable in SF's clothing (The Space Trilogy, by C.S. Lewis)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670522covers-672x372.jpg)

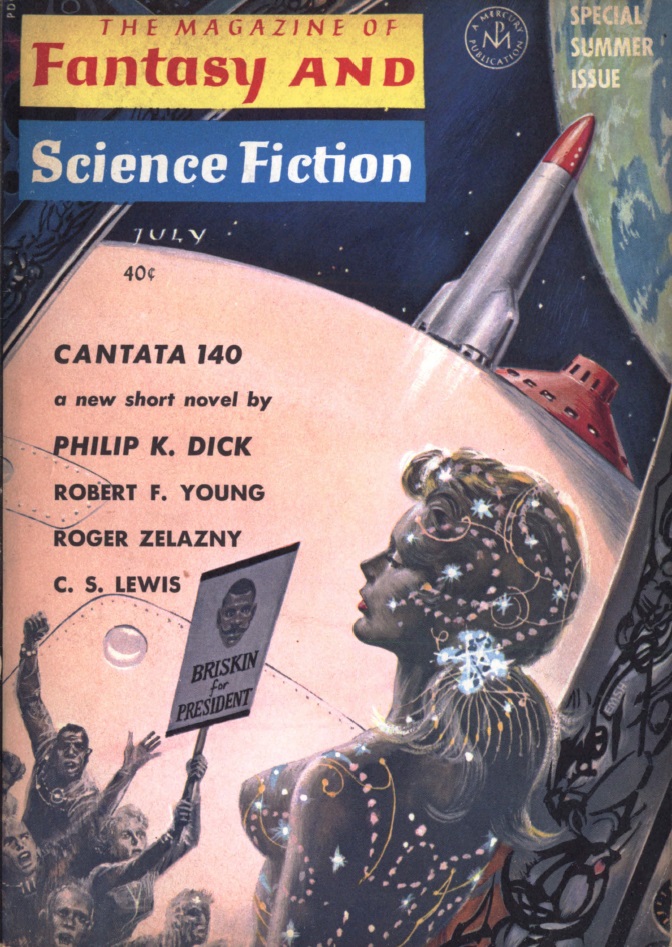

![[June 20, 1964] How low can you go? (July 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640620cover-672x372.jpg)