by Gideon Marcus

There are some months where the space shots come so quickly that there's scarcely time to apprehend them all, much less report on them! Every other day, it seems, the newspaper has got a headling about this launch or that discovery, and that's before you get to the announcements about the impending moon missions.

So, in rapid-fire style, let's see how many exciting new missions I can tell you about on a single exhale (while you stand on one leg, no less…that's a Jewish joke).

A Pair of Yankee Explorers

On August 8th, a Scout rocket took off from Vandenberg Air Force Base (the Western Test Range) in Southern California carrying the two latest NASA science satellites. It was a virtual duplicate of the launch nearly four years ago of Explorers 24 and 25: a balloon for measuring air density in the upper atmosphere, and a more conventional satellite with an array of instruments for surveying the Earth's ionosphere. Affectionately dubbed "Mutt and Jeff", these two craft were sent into polar orbit (hence the Pacific launch site). If you're wondering why NASA is repeating itself, that's because the sun has a profound effect on the Earth's atmosphere. It is important to measure its impact throughout the 11 year solar cycle, from minimum to maximum output, to better understand the relationship between the solar wind and the air's upper layers.

Not much can go wrong with a balloon, but Explorer 40, after deploying its spindly experiment arms, suffered a malfunction. Its solar panels are not delivering as much power as they should. NASA is confident, however, that this will not compromise the mission, which is planned to last more than a year.

Alphabet Soup

Time was, we gave proper names to our satellites. Now it's all acronyms and arcane jumbles of letters and numbers. That's all right. I can decipher them for you!

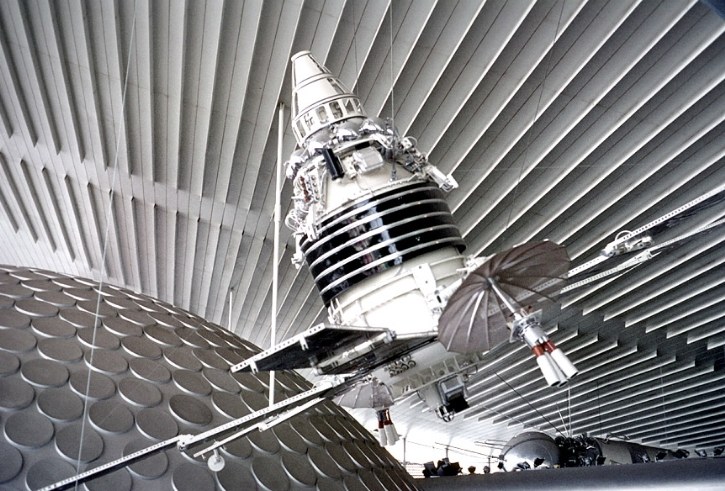

Advanced Technology Satellite (ATS) 4

August 10 marked the launch of "Daddy Longlegs" ATS 4, the fourth of seven satellites in this series.

Some of you may remember ATS-1–you may recall that ATS-1 helped relay the first worldwide "Our World" broadcast last year.

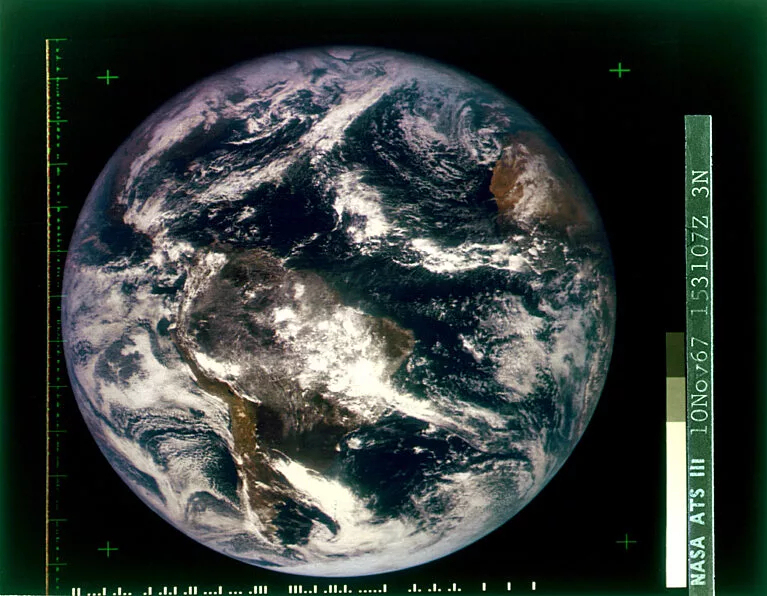

ATS-1 is actually still working, just like its two siblings. ATS-2, launched April 5, 1967 was judged a failure since the second stage of its carrier rocket malfunctioned, stranding it in an eccentric orbit. Still, the several science experiments onboard have returned information on cosmic rays and such in space. ATS-3, which went up November 5, 1967, was the last to ride an Atlas Agena D rocket. Armed with a panoply of experiments, including two transceivers, two cameras, and a host of radiation detectors, that satellite worked perfectly, returning the first color picture of the entire Earth!

ATS-4, unlike its predecessors, is a strictly practical spacecraft, carrying no science experiments, but makes up for it in engineering marvels. One is a a day-night Image Orthicon Camera, a teevee transmitter that would provide continuous color coverage of the world from high up in geosynchronous orbit (i.e. orbiting at the same rate as the Earth turns, keeping it more or less stationary with respect to the ground). Another is a microwave transmitter, turning ATS into a powerful communications satellite like its progenitor

ATS-4 also was to test out a gravity gradient stabilization system, basically using the subtle gradations of the Earth's pull on the satellite's arms to keep it oriented in orbit. Finally, ATS-4 has an ion engine aboard. These drives, perfect for space, work by shooting out Cesium electrons. They are incredibly economical compared to conventional rockets, but their thrust is quite low, meaning they must be fired continuously to have an appreciable effect on velocity.

Sadly, as with ATS-2, ATS-4's Atlas Centaur failed on the second stage, stranding the satellite in a low, largely useless orbit. Well, I guess that's why you launch lots of them!

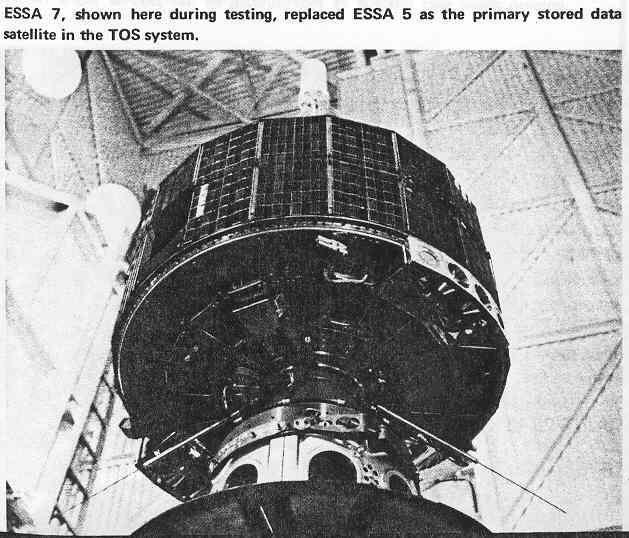

ESSA 7

We haven't given the ESSA series of satellites much love, which I suppose is what happens when a technology stops being novel and instead becomes routine, even essential. After all, who reports on every airplane that takes off anymore?

But it's worth talking about the latest satellite, ESSA 7, launched August 16, to summarize what the system has done for us over the last several years.

There were eleven satellites in the TIROS series of weather craft, the first launched in 1960. In February 1966, with the launch of ESSA 1, the Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA) took over the cartwheel satellites, making the series officially operational.

All of them have worked perfectly, launched into sun-synchronous polar orbits about 900 miles up that circle the Earth from north to south as the planet rotates eastward beneath. So perfect is ESSA 7's orbit that it will cross the equator at virtually the same time every day, drifting from that time table by only four minutes every year.

ESSA satellites have returned 3000 warnings of hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones, reporting not just on the existence but the intensity of these dangerous storms. As of May 27 of this year, ESSA satellites had taken a million photos of the Earth's weather–that's $42 per picture, since the total launch cost of an ESSA is $6 million.

An image of Tropical Storm Shirley taken August 19, 1968

Up in the Kosmos

If we had to cover the launch of every Kosmos (Cosmos) satellite out of the Soviet Union, we'd have to go to a daily schedule. There's such a thing as too much of a good thing, right?

But the Russkies are putting them up on the average of one a week, so it's worth sampling them occasionally to keep tabs on all the stuff they're putting in orbit. Especially since the Kosmos is a catch-all designator, even more broad than our Explorer series. It includes military satellites, science satellites, weather satellites, even automatic tests of the Soyuz spacecraft.

Here's a brief outline of the launches this last month:

Kosmos 230

This is a typical Soviet launch press release:

The Soviet Union launched another Cosmos satellite today and the Sputnik was reported functioning normally, Tass, the official Soviet news agency, said. The device, Cosmos 230, is sending information to a Soviet research center for evaluation.

We know it was launched July 5 into a 48.5 degree inclined orbit, that it soars between 181 and 362 miles above the Earth, and that it's still in orbit as we speak, circling the Earth every 92.8 minutes.

As for what it's for… well, your guess is as good as mine. That said, it's probably not a spy satellite. How do I know? Read on, and I'll show you what a spy sat looks like so you can spot them yourself!

Kosmos 231

The Soviet Union has launched another satellite in its program of exploring outer space, the official Tass news agency said Thursday. It said Cosmos 231 was launched Wednesday [July 10] and is functioning normally. The latest Cosmos is orbiting the earth once every 89.7 minutes in a low orbit from 130 miles to 205 miles. Its angle to the earth was 65 degrees.

Seems innocuous enough, right? Doesn't tell you anything more than the other one. Except…

First tip-off: the angle. A zero degree angle would be along the equator, never leaving 0 degrees latitude. A 90 degree angle is polar, heading due north and south. The lower the angle, the narrower a band of the Earth a satellite covers.

A 65 degree angle is sufficient to cover a wide swathe…including all of the continental United States.

The altitude is quite low, too. The closer, the better–if you want to look at something from orbit.

But the real kicker is this: the spacecraft reentered on July 18, just eight days after launch. Normally, when you send a science satellite up, you want it to stay in orbit as long as possible to get more back for your buck…er…ruble. You only deorbit a spacecraft (and make no mistake–Kosmos 231 had to have been deorbited; its orbit wasn't that low) when there's something onboard you want to get back. Like a person…or film.

We know there wasn't anyone onboard Kosmos 231. The Soviets would have told us. By the way, I'm not the only one who thinks the Kosmos was a spy satellite, taking pictures in orbit and then landing the film for processing. There's a blurb in the July 15th issue of Aviation Weekly and Space Report which says the same thing. And they reached that conclusion before the craft even landed, just based on the orbit!

By the way, if you're wondering what the Soviet spy satellites look like, we actually have a better idea of theirs than ours! We're pretty sure they're based on the Vostok space capsules used to carry cosmonauts. In fact, it's an open question whether or not the spy sat was evolved from the Vostok or the other way around!

Kosmos 232

Launched July 16, its orbital parameters were as follows: 125 to 220 miles in altitude, 89.8 minute orbit, 65 degree inclination. The newspaper article I read noted that the satellite's path was a common one, and predicted the satellite would be recovered in eight days.

Sure enough, it was on the ground again on July 24.

Sound familiar?

Kosmos 233

Here's another oddball: launched on the 18th, the Soviets didn't release news of its orbiting until at least the 20th. It's in a near polar orbit, soaring up to 935 miles, grazing the Earth with a perigee of 124 miles.

That's no spy sat. In fact, I'd guess this one might be a bonafide science satellite, exploring the Earth's Van Allen Belts. But it could just as easily be the equivalent of our Transit navigational satellites or something. We won't know until and unless the Communists publish scientific results.

Kosmos 234

Launched July 30, it soared from 130 to 183 miles up with a period of 89.5 minutes and an inclination of 51.8 degrees. Low orbit? Check. Cryptic announcement describing its purpose as "the continued exploration of outer space"? Check. But the inclination's a bit low. Better wait for more information.

Oh wait. It landed August 5. Pretty sure we know what this one was!

Kosmos 235

Up August 9, down August 17. Orbit went from 126 to 176 miles, period was 89.3 minutes, and the inclination was exactly the same as before–51.8 degrees.

I'm not sure the significance of the different inclinations. Maybe it's a matter of the rocket or the launch location. Generally, the higher the inclination, the more expensive the shot in terms of fuel since the rocket doesn't get the extra boost of the Earth's rotation.

Operator?

It's been a while since we covered the Molniya communications satellites, one of the few Soviet series we do know something about. July 5 marked the launch of the ninth comsat in the series, zooming up to a high, not quite geosynchronous, orbit, where it has a nice vantage of the whole of Asia.

This launch comes less than three months after the orbiting of Molniya H, the eighth in the series. Whether Molniya I is replacing its predecessor, which may have been faulty, or whether the ninth Molniya is simply acting as a backup, is not certain. The latter seems unlikely, though. When Molniya G went up just three weeks after Molniya F, it was widely believed that the Russians had sent up two to make sure they could televise their annual November Moscow parade to the other Communist countries.

That's all folks!

That's the big news for this month. The rest of the year is going to be really exciting, what with the upcoming launch of Apollo 7 and Zond 5. We're about to enter a new phase of manned lunar exploration. That said, we promise to keep covering the significant shots closer to home, too. For us, all space missions are out of this world!

The prime crew for Apollo 7 (l-r) Astronauts Donn F. Eisele, Command Module Pilot; Walter Cunningham, Lunar Module Pilot; and Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Commander

![[August 26, 1968] No time for a breath (Summer space round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680826essa7-629x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1967] Around the World in Two Seconds (<i>Our World</i> Global Satellite Broadcast)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Our-World-1.png)

![[December 20, 1966] Above and beyond (January 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i> and a space roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661220cover-656x372.jpg)