by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

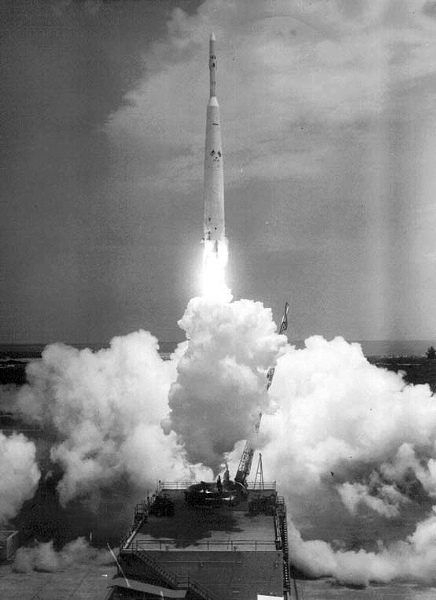

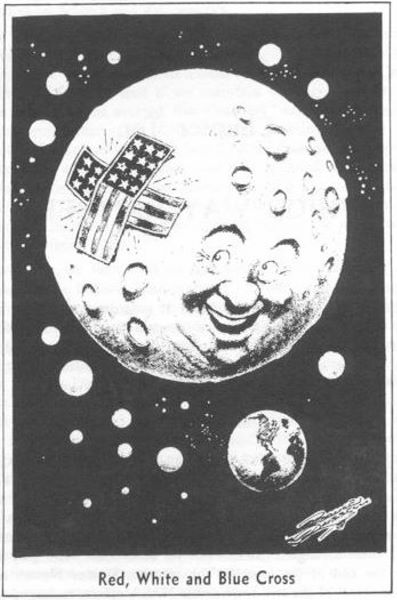

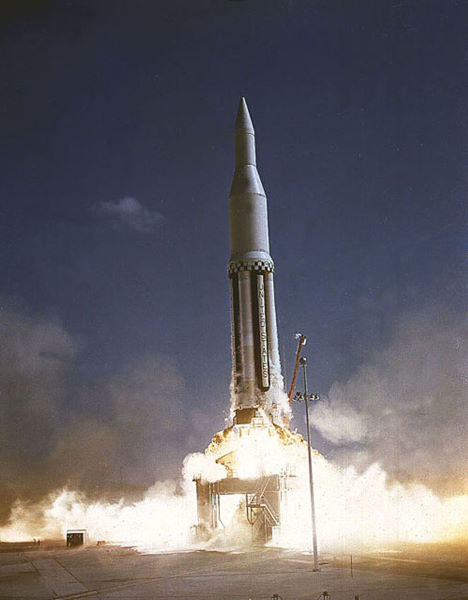

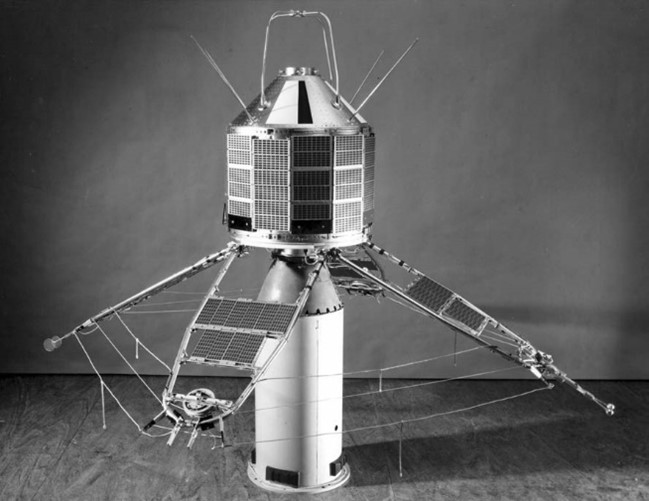

Next week will see the launch of third satellite in the British Ariel programme. Assuming this is successful, it will be significant for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, whilst it is being launched in partnership with NASA in California, it will be the first satellite to be entirely made and tested in Britain, whereas the first two were made in the US. In cooperation between the Royal Airforce, British Aircraft Corporation and General Electric Company, its success would help show that Britain can, if not exactly compete in the space race, at least get a nice chance at a bronze medal.

Secondly, it is carrying five different experiments for UK research facilities, from measuring electron density to atmospheric noise, all of which are going to be important for a more detailed understanding of our world.

One of the most interesting experiments to me is that Jodrell Bank is using it to study medium frequency waves that occur in space. As well as helping understand radio transmissions better this may also help better detect signals coming from extra-terrestrial intelligences. Which is what The Terrornauts is concerned with.

Mr. Brunner…We’re Needed!

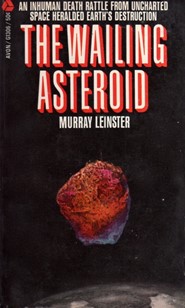

Back in the ancient days of 1960 our esteemed editor gave a rather damning review of the original novel. However, largely this was due to the prose and the story being dragged out and it was noted that “the premise is excellent”. As such, if a good team was assembled it might well make a good motion picture.

Step forward the first member of this team, John Brunner. One of Britain’s brightest SF authors. Whilst, to the best of my knowledge, he has not written a film script before, he is adept at producing both readable space operas and extremely literary works. He reportedly wanted to remove all the dated pulp era material to concentrate on core science fiction ideas and character work.

Next up, a steady experienced hand of a director is needed, enter Montgomery Tully. Director of over 60 films across 4 decades, including last year’s excellent horror thriller Who Killed The Cat? Although not experienced in SF, many of the best productions of recent years have come from experienced directors outside the field. I will take a Godard or Kubrick experiments over another Irwin Allen or Ed Wood picture.

This production is from Amicus studios, the main rival to Hammer studios, with the enjoyable horror anthology Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, the middling Dalek films and…. whatever The Deadly Bees was. Whilst they do not have the budget of their competitor, they have had ambition to try to do interesting films. Could this be their next success?

Added to this an array of talented actors listed on the cast sheet and things seem setup for a great cinematic experience.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

As it turns out, a lot!

Let us start with the plot itself. It begins with people working in a field of current interest to many SF fans, attempting to use high powered radio telescopes in order to attempt to find intelligence life outside of our solar system. Dr. Burke’s team have been working on the project for 4 years but failed to produce any results, to the frustration of Dr. Shore, who is annoyed they are using the equipment on the project. Having just 3 months left to discover a sign of life, they receive a repeating signal from an asteroid.

What is particularly surprising is it is the same signal Dr. Burke heard as a child. At an excavation with an archaeologist uncle, a mysterious black cube was uncovered. He was given it as present and inside he found strange black crystals that hummed. Falling asleep holding one, he had a dream of an alien world. On that world he heard the same sound. As you can probably tell, this is going to require you to accept a lot of coincidences.

After sending a signal back, a spaceship comes and takes the lab away (although not the control room or telescope it was sent from), along with Dr. Burke, his assistants Lund and Keller, and two comedy characters, the accountant Yellowlees and the tea lady Mrs. Jones.

We do have to talk about the odd comic turns. There's no problem with having some light comedy to emphasise the drama and the use of ordinary characters out of their depth is a common charming feature of Nigel Kneale’s SF plays or Hammer Horror films. The issue here is that it is played so broadly in contrast to the po-faced stance of the rest of the cast it sticks out. Charles Hawtrey is a regular member of the Carry-On cast and Patricia Hayes is probably best known for her regular appearances on the Benny Hill Show. I could not help but wonder at times if they had just walked off of those sets temporarily. Just toning down their performances and lightening the others would have done wonders.

Our five space farers find themselves in a structure on the asteroid and spend a lot of time wandering about and solving a series of logic puzzles to prove intelligence (likely inspired by a similar sequence in The Dalek Invasion of Earth), they are given a cube like Dr. Burke received as a child. It turns out to be a store of information on their mission. An ancient race explored the stars and encountered a race only known as “The Enemy” that want to eliminate other intelligent life by using rays that reduce intelligence. The signal from the base indicates The Enemy’s signals are approaching Earth and it is up to these five to use the base to defend humanity.

There is also a brief side trip where Lund trips on to a ‘Matter Transmitter’ and gets sent down to a planet full of green people in togas and shower caps who want to sacrifice her, but this seems largely to be a way to have a traditional pulp action sequence more than anything else. In fact, for such a short film, there is enormous amount of time being wasted. Most egregious is a sequence where they are trying to find a cube to help them and spend ages sampling them all, only to have the real cube presented to them by the unconvincing robot of the base.

Although looks are not everything it has to be said this film looks cheap. Yes, the budget was smaller than Daleks – Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. or Thunderbirds Are Go, but it is at a comparable level to Island of Terror and The Projected Man, neither of which look as bad as this (despite their many other faults). Even BBC episodes of Doctor Who or Out of the Unknown, which work on less than 10% of the budget for similar runtimes, rarely resemble this level of shoddiness.

At the end it looked like we could have a tense and exciting space battle, but instead we have the attacking ship opening to reveal a red torch light and the fortress flailing about like a drunken Octopus.

Finally, the attacking fleet is destroyed but not before the final ship comes to crash into the base. The team manage to use the Matter Transmitter to escape and land in the same archaeological dig the black cube was found by Burke’s uncle. However, not having passports, they are arrested by a local police officer. Given how much The Terrornauts tends towards terrible cliché, it, of course, ends on a bad joke from Mrs. Jones:

I never did much like foreign parts

Hilarious…

Naut The Best Film

As you can probably tell, this is a poor picture. Logic is consistently tenuous. There is barely enough plot to fill a Ferman vignette, instead being reduced to run-arounds. If I didn’t know its origins, I would have assumed this was a fan’s attempt at a Doctor Who script that was rejected by the production team.

But I think its worst sin is it is just incredibly dull. I don’t think this is due to lack of incident, but it is not about anything. There are no themes or interesting ideas I can tease out, it is just some people from Earth put into space to fight invaders, which they do via following recorded instructions.

Even this might have been salvaged if we had good character work but they all as thin as cigarette cards. Burke is the hero who is always right and can apparently do anything. Lund is his assistant who does whatever he says or randomly gets into trouble so she can be rescued. Keller is there for Burke to talk to. Yellowlees is the fussy and cowardly comic relief. And Jones is the ordinary person who does not quite understand what is going on, also for humour value.

They do not have any growth or go on a real quest. There is no significant difference I can see between the people when they leave Earth and arrive back.

In the end I cannot give this production more than one star.

Future Terrors

Coming out very soon (we are continually promised) is 2001, the collaboration between another British SF author and experienced British director. Will this end up meeting the same fate? We shall see…

![[April 28, 1967] Tempest in a Teacup (<i>The Terrornauts</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Title-card-672x372.jpg)