By Jessica Holmes

Welcome back to your regularly scheduled ramblings on Doctor Who, folks. Let's get on with it, shall we?

Today I'm covering a shorter serial, a little two-parter set entirely aboard the TARDIS, where the ship has crashed with no apparent cause, and the crew must work out what happened to the ship and how to fix it before time runs out. With tensions running high, will the crew break apart before the ship does?

I'm making this sound much better than it turned out to be. You'll scream when you find out what the cause of all the problems is. Trust me.

THE EDGE OF DESTRUCTION

In this episode, the TARDIS lands with a bump, knocking our entire crew out cold. As they come to, one by one, it becomes clear something is very wrong with our crew. Wandering about in a daze, they appear confused at their company, as if they've forgotten the last couple of adventures, their relationship to one another, and their personalities.

Shortly after they come to, they make a startling discovery: the TARDIS doors are opening and closing by themselves. Susan begins to fear that there's something aboard the TARDIS with them.

Upon approaching the console, Susan has the most dramatic faint ever put to film. Ian ever-so-gently gives her a fireman's lift and plonks her down on a bed that can't be at all comfortable if you like to sleep in any other position than on your back. I wouldn't get along very well aboard the TARDIS, even if it is wheelchair accessible.

Susan, it seems, still feels a wee bit poorly when she wakes up, given that when Ian comes near her she threatens to stab him with a pair of scissors.

Look, we’ve all had mornings like that, haven’t we?

Now, stabbing Ian would be a rubbish idea. We like Ian. He’s nice. Susan instead screams and cries and stabs the bed, I can only imagine as punishment for it being so dreadfully uncomfortable.

As a highly responsible adult, Ian confiscates the scissors, by which I mean he leaves them lying around for Susan to pick up again.

The Doctor, bastion of logic and reason, thinks it very illogical to consider the idea that someone or something is aboard the ship with them, even though he was unconscious for a good six minutes at the start of the episode (I checked), during which the TARDIS doors were open for an uncertain amount of time, and his companions were either unconscious or highly dazed.

I don't know what planet's logic he's following, because it certainly isn't ours. If I left my front door wide open for a few minutes, I’d almost certainly end up with somebody else’s cat.

Susan returns to her bed with the pilfered pair of scissors, and when Barbara tends to her, a struggle ensues for the potentially deadly implement. Susan is still suspicious that there is something aboard the TARDIS with them, perhaps even hiding within them.

The Doctor manages to get the scanner working, which comes as a surprise, as he and Susan have been unable to touch any part of the console without suffering terrible pain up to now.

When activated, the scanner displays a sequence of images:

First, an idyllic expanse of English countryside.

The doors begin to open, and an unearthly bellow roars outside. The doors close, and we get the next image, an alien world, one that Susan and the Doctor visited recently. I would rather see that adventure than this one.

Then we see a heavily cratered planet, followed by a solar system, followed by what appears to be a galactic belt, which vanishes in a flash of white.

Ian would like an explanation too, but when he asks, the Doctor throws the question right back at him, because while he reckons the idea of something having crept aboard the TARDIS is absurd, apparently the idea that Ian would sabotage the TARDIS of his own free will is not. Why would he sabotage the TARDIS? To blackmail the Doctor into taking him home, of course!

To blackmail. The Doctor. Into taking him home. In the TARDIS. The TARDIS he has supposedly sabotaged. That TARDIS.

I feel like I'm stating the painfully, horrendously, agonisingly obvious here, but this is an absolutely rubbish blackmail plot.

Barbara also points out that it would be wildly out of character for her or Ian to perform any sort of sabotage on the TARDIS of their own free will, and then it's her turn to clutch her head and scream dramatically, because something has happened to the clock.

I think it melted.

That, or the Doctor is a fan of Salvador Dali.

Susan has a bit of a meltdown, too, while Ian looks a bit confused and checks his watch, which, funnily enough, is exactly what I did at that moment.

Once everyone has turned in for the night, the Doctor goes around checking on everyone with his mischievous chuckle, only this time it's a lot more creepy than endearing, and as he bends over the console to do… I don't know, something, somebody grabs him.

Goodness gracious me, who could it possibly be.

And here ends the first part, with the mystery not any closer to being solved, no real action being taken, and everyone being downright useless.

THE BRINK OF DISASTER

A truer episode title has never been written.

So, it turns out it was Ian trying to seize the Doctor, but not to worry, he promptly keels over, so no harm done. Not to the Doctor, anyway. Ian, on the other hand, is in deep trouble.

The Doctor now reckons Ian and Barbara want to steal the TARDIS and fly back to Earth themselves, to which I say: Pardon?

Even if Ian and Barbara were planning to commandeer the TARDIS, how in the world could they? It's not contemporary Earth technology! They could no more pilot the TARDIS than I could nick an aeroplane from the nearest R.A.F. base and fly to France.

Still, it’s enough for the Doctor to make up his mind to throw Ian and Barbara off the TARDIS.

I am frustrated. I dearly and sincerely hope that this is coming through. Because I have already seen that this programme can be much, much better than this.

An alarm goes off, alerting the Doctor to a Thing. I'm calling it a Thing because I never did quite catch what they called it. Faulticator? Faulplicator? Hot Potater? And as it turns out, literally everything is wrong.

For fear of flogging a dead horse I will not be making the obvious joke.

The central column of the console flashes and begins to move by itself The Doctor calculates that they have around ten minutes to live based upon…something, and the crew work out that the machine has been trying to tell them, through the various strange happenings aboard the ship, what the problem is, because as it turns out this funny little big ship has started to think for itself, after a fashion.

The machine could really do with working on its communication skills.

Barbara figures the power at the heart of the machine has been trying to escape— but why? It's like a wounded animal lashing out at anyone who tries to access the controls…except for the scanner.

There's an entire bit of them unravelling the sequence of the scanner images, the long and short of it being that it's representative of their journey so far. Why is the TARDIS trying to take the Doctor for a trip down memory lane? What’s drawing the energy from the core of the TARDIS? What incredible catastrophe has brought this remarkable ship to the brink of destruction?

A stuck button.

The Doctor pressed the Fast Return switch to get back home at the end of the Dalek adventure, and it got stuck.

Are you pulling my leg?

There we have it, folks. Susan nearly stabbed Ian, the Doctor almost abandoned him and Barbara, everyone completely lost their heads and it was just because a little spring was broken and a button got stuck.

So, Ian and the Doctor prise it up, fix it, and Bob's your uncle, off we go.

Yes.

It's really that simple.

So, we're all friends again, having gotten over our inexplicably odd behaviour. The Doctor says he's proud of Susan even though she contributed absolutely nothing and, might I remind you, almost stabbed both of her teachers. Back in my day that was most certainly grounds for expulsion.

Then, having still not managed to arrive on Earth, everyone goes off to play in the snow because we've all forgotten what we're doing.

And behold! Someone with very big feet has been through here.

Looks like one of my eldest brother’s footprints.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Where to begin?

I did not particularly enjoy this story.

This wasn't terrible, though. Don’t get me wrong.

It was mediocre. That's all. Just mediocre.

And I think that might be worse.

Nothing happens. Threads of mystery are half-heartedly picked up, toyed with, and then cast aside in favour of the next idea to pop into whichever character’s head, as if the narrative was being played with by a bored cat. Everyone's having mood swings, and as soon as everyone gets back into character, it's over in a few minutes, because of course it would be!

Everyone in this story was acting very strange and as if they only had a vague grasp of their characters (and on reality itself), and there was no actual cause for it, in the end. Now, a red herring is a good tool in building a mystery, but the red herring does have to have its own explanation within the story. Otherwise, it’s just characters acting weird for the sake of acting weird, and that’s not good writing. I could, if I was feeling very generous, chalk it up to concussion, but it wasn’t consistent enough for concussion, and I’m not feeling generous, so I shan’t.

It's nowhere near as good as The Daleks which I think makes it seem worse by comparison. Thank the stars it was only two episodes and I only lost about fifty minutes or so of my life watching it, plus however long I ended up spending doing the write-up.

I am confident that you will miss nothing by skipping this one. I don't really think the companions come out of this any closer than they were at the end of The Daleks. They were pretty friendly at that point, took about ten steps backwards in their relationship, then in a flash they're all best chums again. It doesn't feel organic. There isn’t enough tension remaining within the group to make the infighting seem justified, and given how nasty it got at one point, how quickly they snap back into being friends makes the whole thing seem pointless. If someone threatened to stab me with a pair of scissors, or throw me out of their car based upon some imagined slight, it’d take me a little while to start trusting them again. I think I’d have preferred it if there really was an entity on board. That would have at least been exciting. Especially if it was controlling one of the crew.

I like to end on a positive note, so I will at least say this: the Doctor admitting how proud he is of Susan was really very sweet, and it was something I'd like to see more of. Hopefully we shall do next time, when with any luck we'll find ourselves an adventure worth the watching.

1.5 out of 5 stars.

![[February 25, 1964] From the Sublime to the Ridiculous (<i>Castle of Blood</i> and <i>The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640225blood-350x372.jpg)

![[February 23, 1964] Songs of Innocence and of Experience (March 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640223cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 21, 1964] For the fans (March 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219cover-665x372.jpg)

![[February 19th, 1964] The Edge Of Disappointment (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Edge Of Destruction)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219stabbystabby-672x372.jpg)

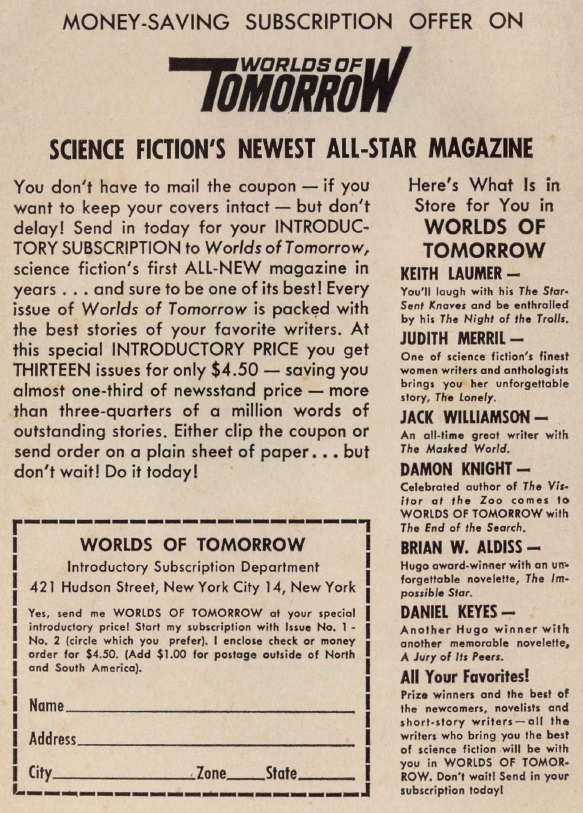

![[February 17, 1964] Breaking Taboos (April 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/6312017cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 15, 1964] Flaws in the seventh facet (<i>Seven Days in May</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640212may-672x372.png)

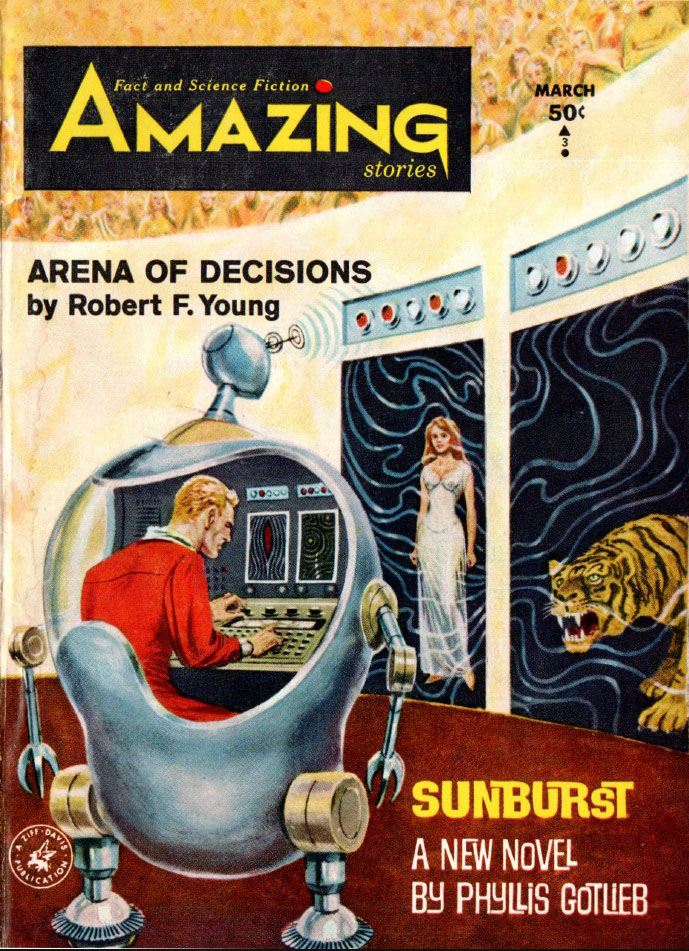

![[February 13, 1964] Deafening (the March 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640213cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 11, 1964] To Gain Ascendancy (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season One, Episodes 17-20)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640211e-672x372.jpg)

![[February 9, 1964] Bargain Basement (March 1964 <i>IF</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640209cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 7, 1964] Journalism and Me (a young woman tries the newspaper biz in the late '50s)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640207chronic1-672x372.jpg)