by John Boston

Better Red than . . . ?

The December Amazing, all business, with the editorial and letter column seemingly dropped permanently , makes a nice-looking package, with a cover by Frank R. Paul shamelessly dominated by near-fire engine red. It’s taken from the back cover of the January 1942 Amazing, where it was titled “Glass City of Europa.” The caption there says "Transparent and opaque plastics make this a wonder city of ersatz science. Transportation is by means of giant, domesticated insects."

by Frank R. Paul

Interestingly, this cover is not only cropped from the original, as is usual, but altered: someone has airbrushed Jupiter from the upper left-hand corner! There’s nothing in its place but more red. Now that’s editing! Of a sort.

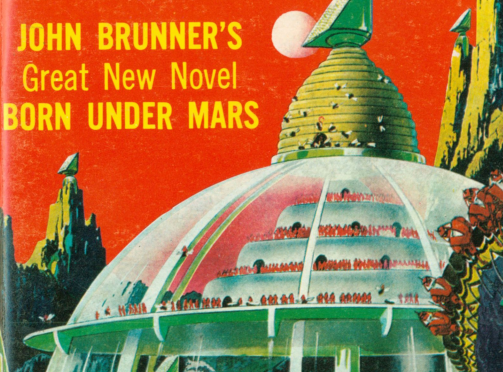

Born Under Mars (Part 1 of 2), by John Brunner

The featured fiction on the cover is the beginning of John Brunner’s two-part serial Born Under Mars. As usual I will withhold comment (and reading) until both parts are available. A quick inspection suggests that this one represents Brunner the capable post-pulp storyteller and not the author in his highly variable philosophical mode, the poles represented by his worthy The Whole Man and his unfortunate mess The Bridge to Azrael.

by Gray Morrow

Vanguard of the Lost, by John D. Macdonald

John D. Macdonald is best known for crime fiction—a lot of it. Since 1950 he has published 40-odd crime novels, most if not all original paperbacks. His current project is a series of novels about a private eye named Travis McGee—eight of them in three years. In all this criminous fecundity it’s easily forgotten that Macdonald was once an up-and-coming SF writer, and pretty prolific at that too. From 1948 to 1952 he published almost 50 stories in the SF magazines, in addition to a number in the borderline-SF pulp Doc Savage, all the while maniacially generating crime stories as well. He used multiple pseudonyms and sometimes had multiple stories in the same magazine issue. In his spare time he cranked out two decently-received SF novels, Wine of the Dreamers and Ballroom of the Skies. A lot of his work was excellent, too; highlights include A Child Is Crying, Flaw, Game for Blondes, and my own favorite, the compact and nasty Spectator Sport, all of them promptly anthologized.

by Julian S. Krupa

Then it all stopped. He had one last story in 1953 in Fantasy and Science Fiction, and since then it’s been all crime, almost all the time. He did appear in the Merril annual “best SF” volume a couple of years ago with a weak fantasy from Cosmopolitan, The Legend of Joe Lee, and in 1962 published The Girl, the Gold Watch, and Everything, a crime novel (rather, a farce with some crime and attempted crime in it) with an SF premise: the time-slowing gimmick of Wells’s The New Accelerator and its numerous successors, including Macdonald’s own Half-Past Eternity, a novella for the pulp Super Science Stories in 1950.

Crime, it appears, paid—at least better than SF. And in fact the SF market of the 1950s could never have accommodated the number of novels he produced. His post-1952 short fiction, meanwhile, was split between the crime fiction magazines and the more lucrative likes of Cosmopolitan, Collier’s, and the Saturday Evening Post.

After that buildup, it’s unfortunate that Macdonald’s Vanguard of the Lost, from the May 1950 Fantastic Adventures, doesn’t amount to more. Aliens have landed! Well, not landed yet, but their fleet of ships is traversing the globe. Larry Graim, statistician by day and SF writer by night, goes up to his building’s roof to check them out, and meets there Alice, a feisty young woman who proves to be the one who denounces Graim’s work relentlessly in the SF magazine letter columns (“the poor man’s Kuttner and the cretin’s van Vogt”).

Graim is disoriented by the fact that these aliens’ rather beat-up-looking, uncommunicative spaceships first seem to be mapping the earth, and then land and release large machines that start building things with no visible sentient direction. It’s completely different from the plots he’s familiar with from the SF magazines, so he and Alice go try to figure out what’s behind the seemingly mindless display. En route there is much mild satire of Everyman reacting to the unprecedented. The denouement is uninspiring and ends on a note of slapstick, to be followed by wedding bells to complete the meet-cute plot. It’s readable and vaguely amusing. Three stars.

The Revolt of the Pedestrians, by David H. Keller, M.D.

The second novelet in the issue is David H. Keller’s first, and probably most famous, story, The Revolt of the Pedestrians (Amazing, Feb. 1928). In the future, everybody is on wheels, all the time. The mania for speed has overtaken everything else; the roadways are progressively more dominated by automobiles; pedestrians first become fair game and then are banned altogether, and hounded out of existence—or so it is thought. By the time of the story, the legs of the ordinary citizen have atrophied, and everyone gets around the house and the office in miniature personal cars. But . . . hidden in the wilderness, a remnant population of pedestrians is thriving, and scheming, and perfecting their science, and soon they shall declare themselves and their demands.

by Frank R. Paul

This of course is all quite ridiculous. But aside from that minor problem, this story is actually pretty good. It’s well paced in a rambling sort of way, very smoothly written, with engaging central characters, with Keller’s soon-to-be-characteristic expositional chunks going down smoothly, and without the cranky and rancorous ideological overtones of some of his later stories. And bear in mind that the absurd extrapolations here are a cruder version of the satirical method that later served Galaxy so well (compare Pohl’s The Midas Plague). Three stars—four if one compares it only to other works of its time.

Dr. Grimshaw's Sanitarium, by Fletcher Pratt

I pinned Fletcher Pratt long ago as one of the more tedious SF writers going (actually, gone: 1897-1956). I remember as a child trying to force my way through his Double Jeopardy, thinking that if Doubleday published it and it was reprinted as a Galaxy Novel, there must be something to it. Then I encountered Invaders from Rigel, in which elephantine extraterrestrials turn humans into metal by manipulating radiation, and realized the futility of persevering with it, or with him. (In fairness, Pratt’s outright fantasy, both his collaborations with L. Sprague de Camp and his unaccompanied work, was much superior.)

The Pratt-fall du jour is Dr. Grimshaw’s Sanitarium, from the May 1934 Amazing. Our hero John Doherty is sent to the sanitarium by his employer for a rest after his courageous thwarting of a train robbery, which left him with some psychological difficulty. It soon becomes apparent that Dr. Grimshaw is a sinister character and there’s something funny going on. He’s turning people into midgets! Soon enough the Doctor gets wise to Doherty and his friends and really gives them the midget treatment, so they end up having to survive in the grass, which is now apparently taller than they are, and subsist on insects that they manage to kill with makeshift weapons (reportedly, June bugs are reasonably tasty but houseflies are disgusting). But now the end is near! Grimshaw’s got a cat, and all is lost. Two stars, barely.

by Leo Morey

Interestingly (sort of), when editors Leo Margulies and Oscar J. Friend solicited self-nominations for an anthology to be titled My Best Science Fiction Story, published in 1949, Pratt submitted this one, though he did acknowledge rewriting it for a more modern audience. I did not investigate the revision.

The Flame from Nowhere, by Eando Binder

by Julian S. Krupa

Eando Binder’s The Flame from Nowhere (Amazing, April 1939) is a routine period adventure story: forest fire proves impossible to stop, turns out it’s really an atomic fire, must have atomic fire-fighting methods, our hero quickly whips them up in a flurry of mumbo-jumbo, making the penultimate sacrifice, two stars. Next!

The Commuter, by Philip K. Dick

by Bill Ashman

Philip K. Dick’s The Commuter, from the August/September 1953 Amazing, during the magazine’s brief flirtation with high pay rates and a stab at higher quality, is one of many facilely clever stories from his early period of prolific glibness. It starts with a small man asking a railroad clerk for a ticket book to Macon Heights, being told there is no Macon Heights, and disappearing. It happens again. A railroad official takes the train and finds it does stop at Macon Heights, which research shows was a proposed development that was rejected by the authorities years ago. So what’s happening to reality? The story, which foreshadows more substantial work by Dick on the same theme, is a trifle with a barb; it effectively conveys the official’s fear for his familiar world and life. Three stars.

He Took It with Him, by Clark Collins

The issue concludes with He Took It With Him, by Clark Collins, actually a pseudonym of Mack Reynolds, who mostly used it for articles in men’s magazines, such as Beat’s Guide to Paris, in French Frills for October-December of this year (Beat? In 1966? What a square.) and Guide to Fallen Women in Sir Knight in 1961. This story is from the April 1950 Fantastic Adventures. Bentley, a selfish rich guy with cancer who’s got a year to live, buys a noted scientist with a promise to build the research institute the scientist dreams of if he will only figure out how to preserve Bentley until such time as he can be revived and cured. The new Institute will be charged with keeping him safe, and also hiding his money, converted to gold and diamonds, until he is awakened to (of course) a nasty surprise that’s not too obvious to the reader. Readable, modestly clever, three stars.

by H. W. MacCauley

Summing Up

So, a middling reading experience—nothing too terrible, most of it at least agreeably readable, one surprise from the unlikely source of Dr. Keller, and the prospect of the Brunner serial pending.

(For an excellent experience, you don't want to miss Part 2 of "The Menagerie", the next episode of Star Trek — join us tonight at 8:30 PM (Pacific AND Eastern — two showings)!!)

Middling indeed, though I may have liked it a little better than you did. I did read the Brunner serial, and it wasn't terrible. It's certainly no "The Whole Man", but it's also better than, say, "The Altar at Asconel".

The MacDonald was fun. It made clear that he not only wrote the stuff, but read it, too. The name-dropping wasn't just random, but showed some understanding of who he was talking about. I did find the mystery of the aliens fairly intriguing. It's not something you see very often, which shows that MacDonald was also capable some innovation in the field.

For it's day, the Kelleryarn was very good. The premise was silly, but the writing was well above the pulpy average. Of course, it was his first story, so he had more time to polish it. Fritz Leiber wrote a few stories in the 50s about conflicts between drivers and pedestrians that could easily have been set in this world a couple of centuries earlier.

The Pratt was very much of its day, silly premise and pulpy stylings. Fairly average in 1934, but badly dated now.

I'd probably give the Binder a third star. A pulpy premise and plot, but I think better written than you give it credit.

The Dick mostly suffers from what has come after it in the same vein. I kept thinking about that Twilight Zone episode with the train stop that doesn't exist. But this was the Dick I remember and liked, before he got into his extremely strange phase. Fortunately, he seems to be coming out of that a little.

The Reynolds, er Collins, was fairly typical of its type. The ending wasn't too obvious, but it wasn't all that surprising either.