[The Journey is joined today by talented author and fan, Cora Buhlert, who expands our coverage of the world significantly…]

by Cora Buhlert

Living in Germany, you cannot help but feel cut off from the wider world of science fiction. Therefore, I always look forward to receiving the latest issue of Galactic Journey in my mailbox, because it allows me to keep up with the latest developments in the genre in the US, the UK and elsewhere.

As a big fan of the Journey, I was thrilled to be asked to give you an overview of the current state of science fiction in Germany. Everybody who regularly follows the news will of course know that since 1949, there are not one but two Germanys: the Federal Republic of Germany, commonly referred to as West Germany, and the so-called German Democratic Republic, better known as East Germany. In the past fourteen years, the border between the two Germanys has become increasingly insurmountable, culminating in the construction of the Berlin Wall two years ago.

I am fortunate enough to live in West Germany and therefore the main focus of this article will be on West German science fiction. However, I will also take a look at what is going on in East Germany.

In the US and UK, science fiction is very much a magazine genre, even if paperback novels are playing an increasingly bigger role. In West Germany, there are a couple of science fiction publishers, such as the Balowa and Pfriem, which specialise in hardcovers aimed at the library market, as well as the paperback science fiction lines of Heyne, Fischer and Goldmann. The three paperback publishers focus mainly on translations, whereas the library publishers offer a mix of translations and works by German authors. Though Goldmann has recently started publishing some German language authors such as the promising new Austrian voice Herbert W. Franke in its science fiction paperback line.

However, the main medium for science fiction and indeed any kind of genre fiction in West Germany is still the so-called "Heftroman:" digest-sized 64-page fiction magazines that are sold at newsstands, gas stations, grocery stories and wherever magazines are sold. Whereas American and British science fiction magazines usually include several stories as well as articles, letter pages, etc…, a "Heftroman" contains only a single novel, technically a novella. "Heftromane" are the direct descendants of the American dime novel and the British penny dreadful – indeed, they are also referred to as "Groschenroman", which is a literal translation of "dime novel".

There is a huge range of "Heftromane," covering various genres. The most popular are probably the western and romance, with subgenres such as aristocratic romance, alpine romance or doctor and nurse romance. Crime and mystery series are also popular, as are adventure and war stories. By comparison to these flames, science fiction is still a small but growing flicker.

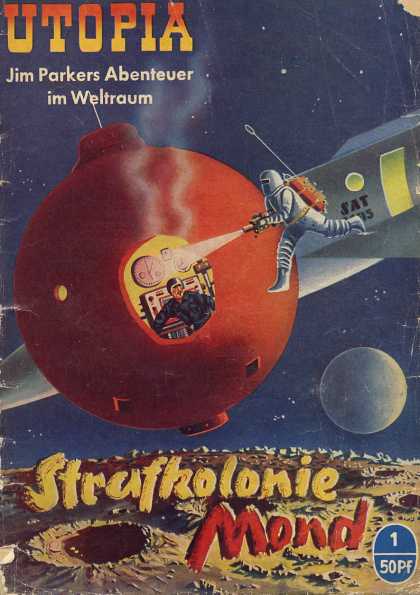

There were shortlived German language science fiction "Heftromane" published in the late 1940s in Germany, Austria and in Switzerland. However, the postwar era of (West) German "Heftroman" science fiction began exactly ten years ago in 1953, when Pabel, one of several publishers of "Heftromane", introduced its latest series Utopia – Jim Parkers Abenteuer im Weltraum. Though the first issue was anything but utopian, considering that it was set in a penal colony on the moon, where convicts are forced to shovel nuclear waste. The protagonist is Jim Parker, an American space ship commander in the employ of the Atomic Territorium. Together with his German pal Fritz Wernicke, Parker spends the next 43 issues bouncing around the solar system, while tangling with the villainous "Yellow Union". The Jim Parker stories were written by one Alf Tjörnsen whose identity remained mysterious for many years. Though Tjörnsen has recently been revealed as a pen name for author Richard Johannes Rudat.

Compared to American science fiction, the Jim Parker stories felt old-fashioned, a throwback to the 1920s and 1930s. The science was often laughably bad as well. And so, after 43 biweekly issues of Jim Parker's adventures in space, Utopia changed its name to Utopia Zukunftsroman and began alternating standalone novellas with the Jim Parker stories. Initially, those standalone stories were written by German authors, usually operating under house names, but from 1955 on, Utopia also published translations of American science fiction by authors such as John W. Campbell, Leigh Brackett and Murray Leinster, as well as Britishers like Eric Frank Russell. Due to the constraints of the "Heftroman" format with its 64 page limit, these translated works were heavily abridged. Nonetheless, to many German fans they served as the first introduction to the wider world of American science fiction.

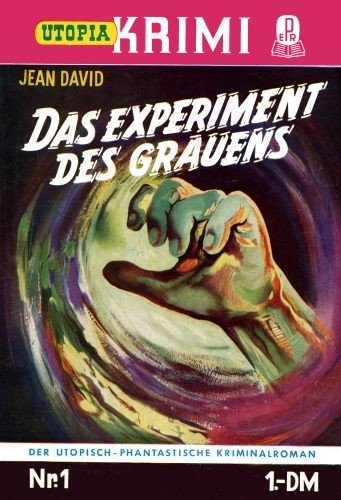

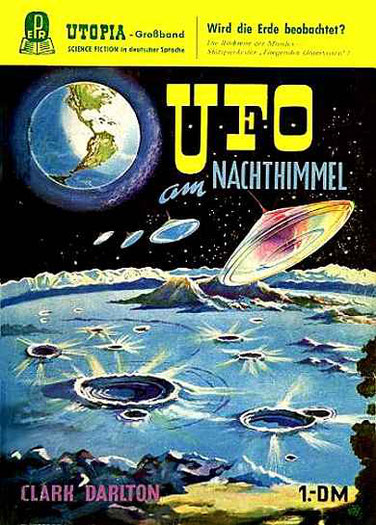

The success of Utopia Zukunftsroman spawned several spin-offs. The first of these was Utopia Großband, a thicker 94-page "Heftroman" which debuted in 1954 and allowed for publishing translations of American science fiction novels, though once again many novels were mercilessly cut to fit the format. Utopia Sonderband, later Utopia Magazin, an anthology magazine in the style of the American science fiction magazines, followed in 1955. The final spin-off of the Utopia family was Utopia Kriminal, which debuted in 1956 and billed itself as a series focussed on futuristic crime novels, inspired by the success of the Edgar Wallace thrillers with their mixture of suspense, science fiction elements and outright horror. Utopia Kriminal published a lot of translated weird fiction by writers such as Frenchman Jean David and Americans Norvell W. Page and A. Merritt.

However, after its initial success Pabel's Utopia franchise has fallen on hard times of late. Utopia Kriminal and Utopia Magazin were cancelled in 1958 and 1959 respectively and Utopia Großband followed this year. Utopia Zukunftsroman is still hanging on for now, though the quality of the authors and stories translated has declined notably in recent years.

The reason for this is increased competition in the German science fiction market. Inspired by the success of Utopia, the "Heftroman" publisher Moewig launched its own science fiction series Terra Utopische Romane in 1957. The format was similar to Utopia Zukunftsroman, a mix of standalone science fiction novels by German authors and translations of American science fiction. However, the imitator quickly eclipsed the original, for Terra offered higher quality translations and quickly snapped up the A-list of American science fiction authors, leaving only second and third rate works for its competitor Utopia. Indeed, in some cases one novel in a series would be published under the Utopia banner, while the sequel appeared in Terra, to the frustrations of many readers. Like Utopia, Terra also spawned two spin-offs. Terra Sonderband, a thicker 96-page 'Heftroman" similar to Utopia Großband, premiered in 1958. And only last year, the reprint series Terra Extra debuted.

West German genre readers in general and science fiction readers in particular tend to be very americanophile. And so "Heftroman" publishers quickly noticed that translations of American science fiction tended to sell better than works by German authors. The fact that homegrown science fiction wasn't always up to the snuff, especially when compared to the best of American science fiction, did not help either. So magazines eventually stopped publishing original science fiction by German authors and focussed solely on translations. As a result, it became very difficult for budding German science fiction writers to persuade a publisher to take a chance on their work.

One of those budding German science fiction writers was Walter Ernsting, who first encountered science fiction while working as a translator for the allied forces after World War II and quickly fell in love with the genre. In 1955, Ernsting cofounded the Science Fiction Club Deutschland, Germany's biggest fan club. By the mid 1950s, Walter Ernsting was working as an editor and translator for the Utopia line, but was unable to get his own novels published. So the enterprising Ernsting passed off his own writing as the work of a fictional British author named Clark Dalton and promptly had it accepted. Clark Dalton's stories were well received by the readers of the various Utopia titles and so Ernsting kept on writing and publishing as Clark Dalton, even after the secret of his identity was revealed. Nor was Walter Ernsting the only German writer who circumvented publisher prejudice by writing under a British or American sounding pen name. Instead, westerns, science fiction and crime 'Heftromane" are full of German writers pretending to be Americans with varying success.

In 1958, Ernsting left Pabel for competitor Moewig to work on the Terra line of 'Heftromane". Terra was more open to publishing German authors than Utopia and one of their stars was K.H. Scheer, a prolific young author who had gotten his start writing for the library hardcover lines of Balowa and Pfriem.

Together, Ernsting and Scheer came up with the idea to create an ongoing science fiction series focussed on the adventures of a central character. Now "Heftroman" series following the exploits of a single character are popular in the crime genre – the best know example is probably G-Man Jerry Cotton, which chronicles the adventures of a fictional FBI agent in New York City – but were largely unknown in science fiction following the demise of the rather bland Jim Parker. Nonetheless, Ernsting and Scheer persuaded Moewig to take a chance on their idea and retreated to Ernsting's home in the idyllic Bavarian village of Irschenberg to hammer out the details and come up with a rough plot outline for the first ten issues.

The result, entitled Perry Rhodan – der Erbe des Universums (Perry Rhodan – Heir to the Universe), debuted on September 8, 1961 and has quickly become a sensation in the twenty months since, turning into West Germany's most successful "Heftroman" series with a monthly print run of approximately one million. Unlike the old-fashioned and rather dull Jim Parker stories, Perry Rhodan literally starts with a bang and only keeps getting better. Initially planned to last between thirty and fifty issues, Perry Rhodan is now closing in on issue 100. If the authors manage to keep up the quality, I can see this series lasting a very long time indeed.

And that's it for today. Next time, I'll give you an overview of the Perry Rhodan series and the competitors spawned by its enormous success. I hope you have enjoyed!

Thanks for the article! I've seen a few Perry Rhodan issues in local swap shops. Local USAF airmen sometimes bring them back after being stationed in Germany. I've examined them curiously, but alas, I can't read German… while we see plenty of SF from British or Australian authors, we see almost none from non-English-speaking authors. Perhaps someday, particularly now that new stories seem to be in short supply, someone will step up and start translating some of those stories.

Just a nit pick: the talented Eric Frank Russell is British, though widely published in the USA. We don't see him quite as much as we used to, though.

Thank you for this well written and interesting post. I'm sure Perry Rhodan will eventually be available in English; let's hope there's plenty of other German sf to follow.

Thanks for an interesting report!

Soldiers and sailors are generally a good source of overseas SF. American SF magazines and comics occasionally show up in second hand and swap shops here, courtesy of the American GIs stationed in and around Bremen and Bremerhaven. So I'm thrilled to see that a few Perry Rhodan issues made it to the US. I also hope that the series will be translated soon, because I'm sure that international readers will enjoy it.

Also my bad about Eric Frank Russell's nationality. His stories occasionally show up in the pages of Utopia and Utopia Kriminal and I always enjoy them.

Well, it's not like there's some easy way to look information like that up. The "Who's Who" books at the library don't seem to mention many science fiction authors.

I knew Russell was British because it was mentioned on the cover of one of his books. Same for John Brunner or Colin Kapp. Others, like E.C. Tubb, I only found out because his nationality was mentioned in some of the British SF magazines that occasionally show up locally.

An excellent summary and a far better job than I could have done. Despite having been in Germany pretty much since right after the War, I managed to miss a lot of this. No doubt in part to a bit of snobbery on my part towards Heftromane. The few I dipped into offered mostly translations and rather poor ones at that.

Of course, literary translators tend to be at the bottom of the heap when it comes to remuneration and most of the talent winds up doing business, legal and technical translations. Actually, the finest literary translator I've seen is the woman translating Disney comics. Political pressure may force her to make Donald Duck a little brighter than he is in the US, but she is generally worthy of Carl Barks.

In any case, xenophilia is rather widespread in West German popular culture. A dozen years of repression certainly contributed to that and up until a few years ago most Germans were more focused on rebuilding the country and the economy. Right now, even the pop singers are mostly foreigners (including a couple of former US and UK soldiers).

I have looked at some of the Perry Rhodan stuff and have thoughts. But I'll save that for next time.

Erika Fuchs, the lady who translates the Donald Duck comics is indeed excellent, even though she works in a medium that is even more disdained than "Heftromane".

I also hear you on the poor pay for literary translators. There is a reason I do technical and legal translations.

[Question from the future: Was Heyne already inserting soup and tea ads into the narrative at this point?]

No soup and tea yet, but ads for banks (well, one bank) and saving bonds.

Welcome to the club, Cora! You'll going to be fine here!!! Let us hope you find some Beatles in German somewhere!!!

Thanks, Mike.

Well, the Beatles spent enough time in Hamburg performing on the Reeperbahn (and how I wish I would have gone to see them then), so they should certainly be able to understand and speak a little German.

A fine, interesting overview. Thanks, and I'm looking forward to your followup(s).