by John Boston

Wishing Waiting Hoping

Can it be . . . drifting up through the murk, like a forgotten suitcase floating up from an old shipwreck . . . a worthwhile issue of Amazing?

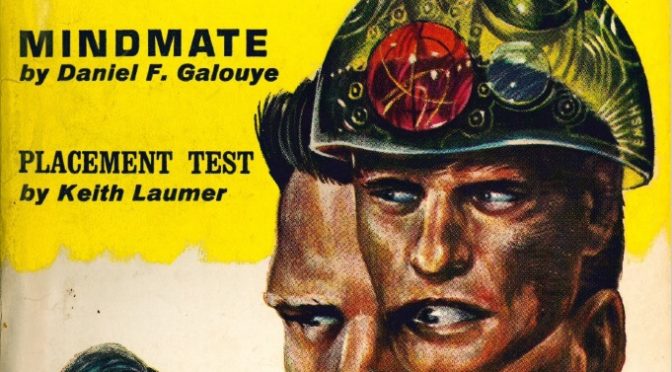

You certainly can’t tell by the cover, which is one of the ugliest jobs ever perpetrated by the usually talented Ed Emshwiller—misconceived, crudely executed, and it doesn’t help that the reproduction is just a bit off register.

by Ed Emshwiller

Mindmate, by Daniel F. Galouye

This hideous piece illustrates Mindmate, an amusingly hokey long novelet by Daniel F. Galouye, an improvement over his last two pieces in Amazing if not up to the standard of his Hugo-nominated novel Dark Universe. In the near future, the Foundation for Electronic Cortical Stimulation, a/k/a the Funhouse chain, is raking it in selling ersatz experience, but is being chivvied by the Hon. Ronald Winston, chairman of the House Investigative Subcommittee on Cultural Influences, who thinks the Funhouses are addictive and should be stopped.

by Ed Emshwiller

So the Funhousers do the only sensible thing—they kidnap Winston and, before killing him corporeally, use their technology to install him as a secondary personality in the brain of protagonist Sharp, who has been surgically altered to be a dead ringer for Winston. It’s Sharp’s job to subvert the Subcommittee’s investigation, though he’s actually thinking of playing a double game.

Sharp’s access to Winston’s memories and habits permits him to impersonate Winston quite successfully, to the point where he sometimes wonders whether he or Winston is really in charge. And that, along with his mixed motives, sets the theme for the story: he’s not the only one playing a double game, or the only one with a double personality and questions about who is dominant. The attendant rug-pulling is executed reasonably well, though the author cheats a little: which personality emerges as dominant seems determined by plot needs and not by any identifiable aspect of the invented technology. And it’s all acted out in the slightly incongruous context of a gangland melodrama. But it’s sufficiently well turned and entertaining to warrant some generosity. Four stars.

Placement Test, by Keith Laumer

by Virgil Finlay

There are two other novelets. Keith Laumer’s Placement Test is one of his aggressively dystopian pieces, similar in degree of oppression but much different in mood from The Walls in the March 1963 Amazing, and less effective. In a hyper-stratified future society, protagonist Maldon, who has done everything by the book, is excluded from his chosen career path through no fault of his own, relegated to Placement Testing for a menial future, and, if he doesn’t like it, Adjustment (of his brain).

Instead of accepting his fate, he rebels, and through a combination of chutzpah and chicanery manipulates the rigid and stupid system to get what he wants . . . only to be told (here’s a revelation as massive as the cliche involved) that it was all a set-up, his rebellion was the real placement test, and he’s going to be a Top Executive (sic). The hackneyed gimmick is offset by Laumer’s usual propulsive execution, so three stars for competence. But if this is Laumer’s placement test . . . he’s not quite as promising as we might have thought from The Walls, It Could Be Anything, and others.

A Game of Unchance, by Philip K. Dick

by George Schelling

The third novelet is Philip K. Dick’s A Game of Unchance, set among colonists on a Mars every bit as unrealistic as Ray Bradbury’s, but much more depressing. A spaceship lands at a settlement, promising a carnival: “FREAKS, MAGIC, TERRIFYING STUNTS, AND WOMEN!”—the last word painted largest of all. But the colony has just been fleeced by another carnival ship! This time, though, the colonists have a plan: their half-witted psi-talented Fred can go to the carnival and win the games with the most valuable prizes.

The prizes turn out to be dolls with intricate internal wiring (microrobs, they’re called), which attack and escape, and later prove bent on harm to the colonists, wiring up the local fauna and the livestock. The UN says the colonists will have to evacuate while they flood the area with poisonous gas; then a higher-powered UN guy shows up and says that they will probably have to evacuate Mars entirely in the face of this extraterrestrial invasion, for that is what it is. At story’s end, yet another carnival ship has shown up—this one with prizes consisting of little mechanical devices claimed to be “homeostatic traps” that will catch the little things the colonists can’t catch themselves—and at the end, they are falling for it.

In outline, this sounds like a tight little piece of irony, but on the page it’s quite atmospheric. Dick has become hands down SF’s master of dreariness. (“The night smelled of spiders and dry weeds; he sensed the desolation of the landscape around him.”) But more than that, he is a master of a particular kind of horror, the horror of being trapped, not necessarily physically, but in events and situations that can only have a bad end and that his characters cannot turn away from. The fact that some of the situations (like this one) make very little sense does not detract from their power; this is a sort of dream logic at work. It doesn’t work for everybody, but for my taste, four stars.

The Mouths of All Men, by Ed M. Clinton, Jr.

by McLane

Ed M. Clinton is a very occasional SF writer, with eight stories scattered over the past decade, almost all in second-tier magazines. In his short story The Mouths of All Men, Soviet and American astronauts are launched simultaneously, intending to meet in space and return together in a show of brotherhood, but while they’re en route someone triggers World War III, destroying humanity. So they match velocities, dock, and immediately try to kill each other; then they calm down, show each other their pictures of their now incinerated families, inscribe a proclamation on their viewport, and purposefully botch re-entry so they’ll be killed on the way down. This is more of a harangue than a story—not a badly done harangue, but the sentiments are quite familiar to SF readers, and starting to get that way for everyone else. Two stars.

The Scarlet Throne, by Edward W. Ludwig

by Blair

The Scarlet Throne by Edward W. Ludwig, a little more prolific but about as obscure as Clinton, is another Message story, this one less well done than Clinton’s. Esteban, the patriarch of a poor Mexican family who lives near a desert rocket launching facility in the US, is troubled by the fact that space is being conquered while his family and his neighbors still lack indoor plumbing, and decides to take his message to the launch site where the President will be in attendance. He doesn’t get far. The story ends with a crude but appropriate joke. The worthiness of the message is overtaken by the story’s heavy-handedness and the rather patronizing portrayal of the Mexican family. Two stars.

Operation Shirtsleeve, by Ben Bova

Ben Bova soldiers on with Operation Shirtsleeve, discussing how to transform Venus and Mars so we can walk around in our shirtsleeves on them—i.e., terraform them, though Bova avoids this term for some reason. Instead, he uses “shirtsleeve” as a verb at least once. I don’t think that usage will stick. Anyway, the answers, respectively, are bombard Venus with algae and bombard Mars ith energy and hydrogen. (I am simplifying a little bit.) It’s the usual fare of interesting information presented dully.

Bova does venture outside his specialties with one observation: “While the moon has some political and perhaps even military advantages, Mars is too far away for any nation to attempt to reach single-handedly. Manned expeditions to Mars will probably be international efforts supervised by the United Nations.” I wonder if he’s giving any odds. Bova then concludes: “The real question is: Why bother? That is a question that can only be answered by the men who actually land on Mars.” I would think that the people who will pony up the trillions of dollars or other currency needed to pay for this project, and their representatives, might have something to say about it too. But the fact that Bova is even asking this question gets him a grudging three stars.

In Conclusion

So: nothing terrible, everything readable, and a couple of items distinctly above average. Celebrate! . . . while you can.

Next month . . . Robert F. Young.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

Not a terrible issue, but I'm somewhat less enthralled than John.

I've said on many occasions that I just don't really connect with Galouye's work. The writing here was decent and the plot, though rather implausible and occasionally confusing, was mildly interesting. But there seemed to be a glass wall between me and the story, keeping me from really engaging with it.

The Laumer was definitely not his best work. This one went on too long, and the protagonist should have smelled something funny going on, what with all the amazing coincidences and strokes of luck. I spotted the ending ages before the story got there. It was also reminiscent of another story not too long ago, I think by Ron Goulart, where someone got reclassified and eventually went off to live in an old bomb shelter.

Phil Dick is a writer I once enjoyed, but whom I have really gone cold on. This one was a little better than a lot of his recent output. At least we're spared weird presidential politics (well, until we get to F&SF anyway), and the characters aren't quite as unrelievedly stupid as in many of his recent stories. Honestly, I often wonder how many times they have to try putting on their shoes before they get them on the right feet. We're also spared a horrible, dying marriage for once. Not much story, though.

Clinton lost me right from the beginning. I had a lot of trouble accepting the murderous rage of the two astronauts. It felt like an unrealistic reaction, but may that's just me.

I can't imagine that "The Scarlet Throne" will be well received in a science fiction magazine. While it does address an issue we should be mindful of and brings up an argument often made against the space program, one would think that if not Esteban himself, then many of his friends and family would have found employment in the building of that large launch facility in a seemingly remote area. It should have brought a lot of money into their community.

Ben Bova continues to improve as a popular science writer, but he still has a way to go. This one was marginally interesting, but he sure made it all sound so easy.

Finally, Bob Silverberg's review column. I know that our John purports to be a teenager from Kentucky, but has anyone ever seen John and Silverbob in the same room? The tone of the acerbic comments in the column on Burroughs and Otis Kline should seem awfully familiar to the readers of this zine.

I enjoyed this issue fairly well, even if there were no great classics.

"Mindmate" was quite readable, but suffered not only from plot logic, as others have said, but for the distasteful implication that the antihero sexually assaults the antiheroine.

"The Mouths of All Men" had a point to make, but ruined it with the most unbelievable behavior in any characters I've ever seen. From deadly enemies to blood brothers in a single second was hard to believe.

"Placement Test" kept my interest as a satiric comedy more than as a serious adventure, despite, as said, a very familiar ending.

"A Game of Unchance" wasn't bad, if a little thin. I see the point that DemetriousX makes about Dick's characters, but I kind of turn it around. I like the fact that the people in his stories are very ordinary, often struggling laborers, maybe not very bright, with psychological problems. It's a refreshing change from mighty barbarians and firm-jawed spacemen.

"The Scarlet Throne" makes a very important point about the Haves and the Have Nots. I like the fact that the protagonist only triumphs internally, and not over the Haves. It was probably my favorite story in the issue.