by Ida Moya

[Meet our newest fellow Journeyer, Mrs. Moya, whose technical background is as enviable as it is fascinating. Given the whirlwind pace at which computer technology is advancing, I thought our readers would like to get, straight from the source (as it were), an account of Where We Are Today…]

Hello, fellow Travelers. My journey to date has been both a long and short one. Long in that I've come a long way since I first started as a typist at an institution you might have heard of: Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. And short in the fact that, well, I'm still here, now employed in the Lab's technical library. I’ve been around these New Mexico labs for nearly twenty years, since they built the first atomic bombs which ended the war.

I started at Los Alamos as a typist, creating memos and reports for the scientists. I learned how to type in high school, a skill that has taken me a long way. I was on the Hill in the beginning, in 1943, when there were only a couple of hundred people were working there. By 1945, there were over 6000. I’ve done a lot of things in these twenty dusty years at Los Alamos. Most of my work has been in the library, helping the scientists and engineers find the documents and information they need in order to get their work done. I’ve seen a lot over these years, and learned quite a bit about science and computers to better help the scientists get things done.

I can tell you more about Los Alamos and Project Y, which until now have been the hush-hushiest of subjects, because just this year a book came out — Volume 1 of the History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission: The New World 1939-1946.

This blockbuster new report, designed by esteemed colleague Marilyn Shobaken of Penn State, where it was published, has all the science archives in New Mexico and beyond buzzing. She was so involved with the production of this document that her name is even included on the verso, right after the Library of Congress catalog card number 62-14633.

That's just background. I promise I will tell you more stories of Project Y and the Hill later, but for now, let me tell you about my current work. It involves the development of computation and how these new transistorized computers will take us into space. I’m not flying into space myself, but the work I do is helping those brave men get to the moon. This is an incredibly exciting project to be a part of, and I’m glad that NASA is not secret. So let me tell you about some of the competitive scientific and technical developments that Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory is leading.

Just last month, on December 7, 1962, the University of Manchester in the UK commissioned the Atlas computer, said to be faster than even the newest IBM computers — the Stretch, the 7090, and the 7094. However, one thing the Atlas computer doesn’t have is an industry behind it. Manchester made this one experimental machine, and have two others in the works; that’s it.

At Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, we acquired the first IBM Stretch computer in 1961. This new transistorized computer was supposed to be 100 times faster than IBM’s previous vacuum-tube based computer, the IBM 704. The Stretch turned out to be only about 35 times faster, so IBM considers it a failure.

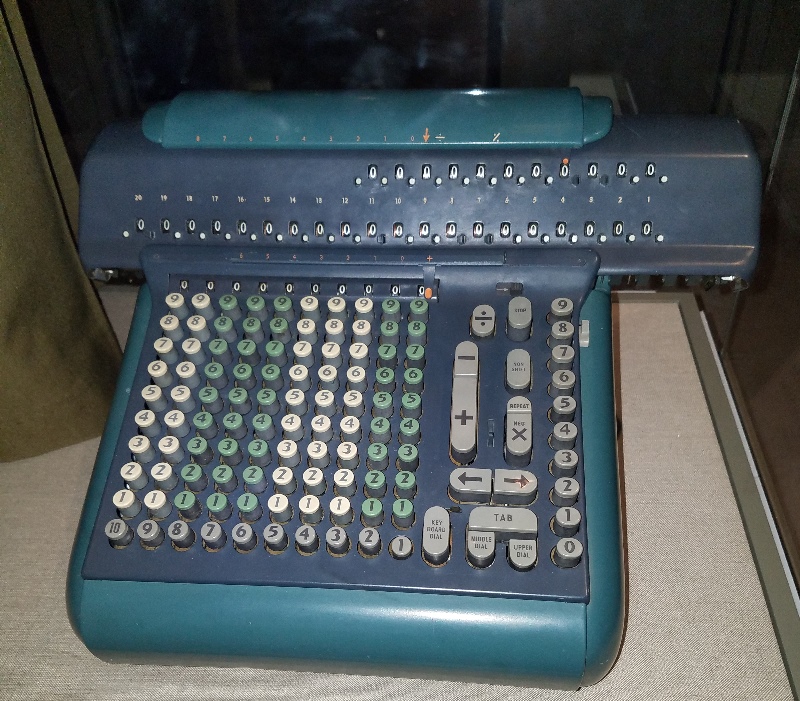

Still, the Stretch is faster than the gals in the human computer facilities, pecking away on their baby-blue Marchant electromechanical calculators. I did this for a time before we got our electronic computers; a tiring and thankless job that had to be done accurately in makeshift buildings in the high desert. Now we program our computers in FORTRAN, in air-conditioned rooms. If you have the aptitude, I highly recommend you learn to program computers using this innovative formula translating language. The space race needs more capable computer programmers (and it's not just for women, no matter what the engineers might tell you).

IBM made a few more Stretch computers, all for governmental customers. The National Security Agency has just installed the next one, and others are being prepared for our sister project at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, as well as the Atomic Weapons Establishment in England, and the US National Weather Service. That's about it, though. As I said, IBM deems this marvel a failure.

However, IBM has learned from this exercise, and has turned their considerable manufacturing prowess to the IBM 7090 and IBM 7094 computers. IBM has factories churning these out by the dozen. As I write, two IBM 7090 computers are installed at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, calculating trajectories for NASA’s Mercury program. These 7090 computers are also being used by rocket scientist Wernher von Braun to simulate flight trajectories in aid of the design of the Saturn rocket system, the rocket that is going to take Americans to the moon. Four more IBM 7090 computers are being used by the Air Force for their Ballistic Missile Early Warning System. There is even an IBM 7090 installed at the Woomera Long Range Weapons Establishment, as part of the Anglo-Australian Joint Project, also used to calculate rocket and missile trajectories. America’s industries are not far behind; two more IBM 7090 systems are being used by American Airlines for their forward-thinking SABRE flight reservation system. Imagine, soon even regular people like us will be able to experience the glamour and sophistication of air travel, as new jet and computer technologies put the price of a ticket within affordable reach.

So, Manchester U.K. may have the “fastest” computer in the Atlas, but the United States has the lead in building an entire industrial infrastructure to deploy fast computers all over the country and free world. Healthy competition with our allies is fine, but what we really need to do is win the space race against those godless Russian communists. The American people will prevail in space, in no small part thanks to FORTRAN and IBM computers.

I'm proud to be a part of this adventure, and now, as part of the Journey, I look forward to bringing you along with me!

—

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Check your mail for instructions…]

Fascinating article. Thanks for all your hard work on so many important projects!

Thank you for the article and welcome. And the photos are great, too.

Boy from Gunga Din to Ben Casey and on, Jaffe had quite a run.

FORTRAN is just like learning typing. I encourage you, women and men, to learn this language that can be used to communicate with computers.

While women get to do the hard work behind the scenes, I notice that it's only men who get to travel to outer space. I hope the situation will change before too long.

I think it's important for young people to have exciting role models to look up to. I also think that women will be accepted into astronaut training soon; Americans are slowly coming aware and pressing for equity in many domains. You ain't seen nothing yet.

That said, there are hundreds of thousands of people — scientists, engineers, technicians, librarians, secretaries — doing the hard work to make these space flights happen. Astronauts are about .01 percent of this team. I think young Americans, men and women, all races and creeds, should have role models in the varied roles supporting our amazing race to the moon.