by Margarita Mospanova

Long time no read, dear readers!

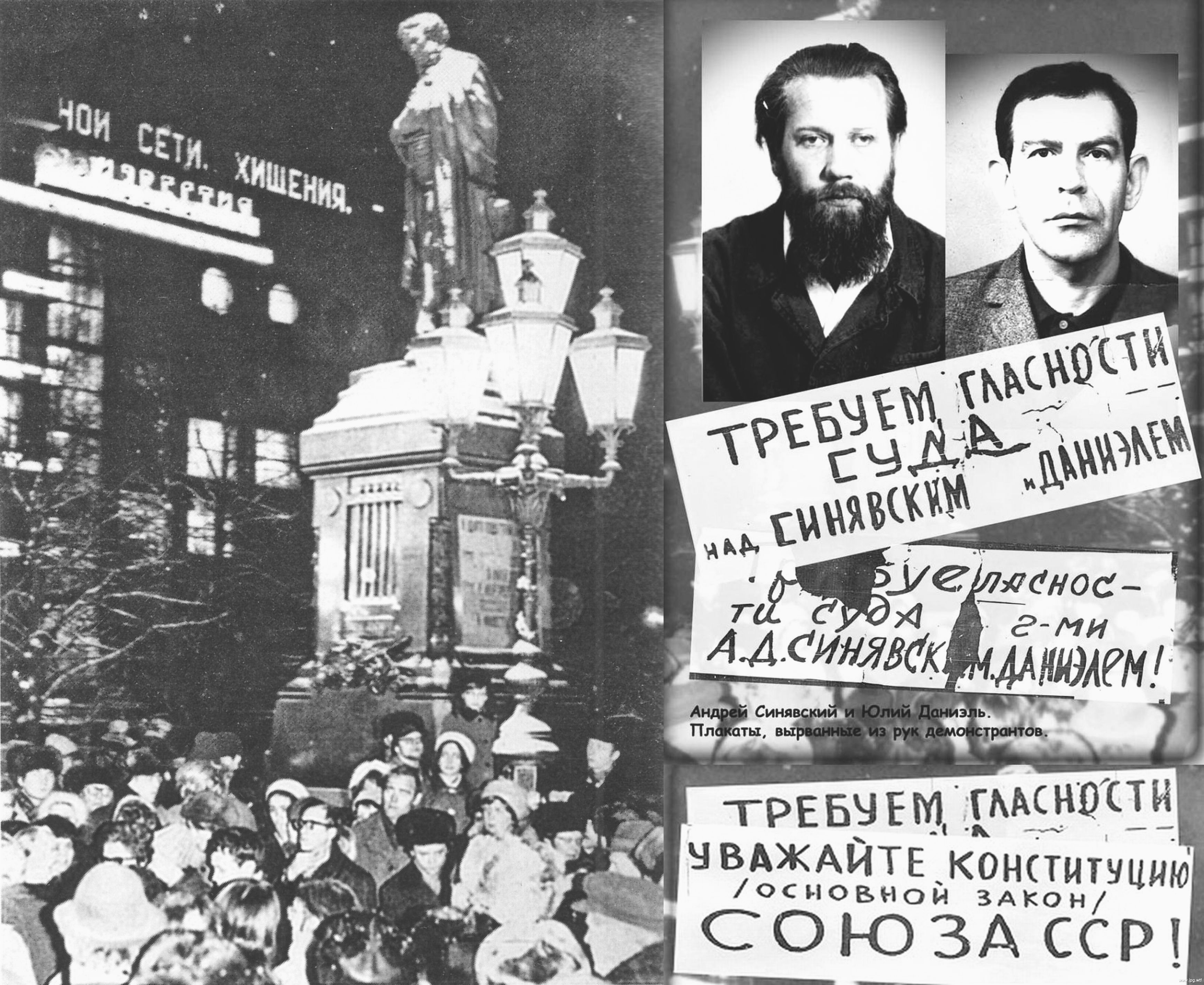

My dearly beloved, but monumentally aggravating home country has once again done what it has been doing since its unfortunate conception — the USSR has arrested another pair of writers that happened to disagree with some of its tenets. The court has yet to pass judgement but there is very little doubt the case will not go in favor of the accused, even despite the very public demonstration in Moscow in their defense on December 5.

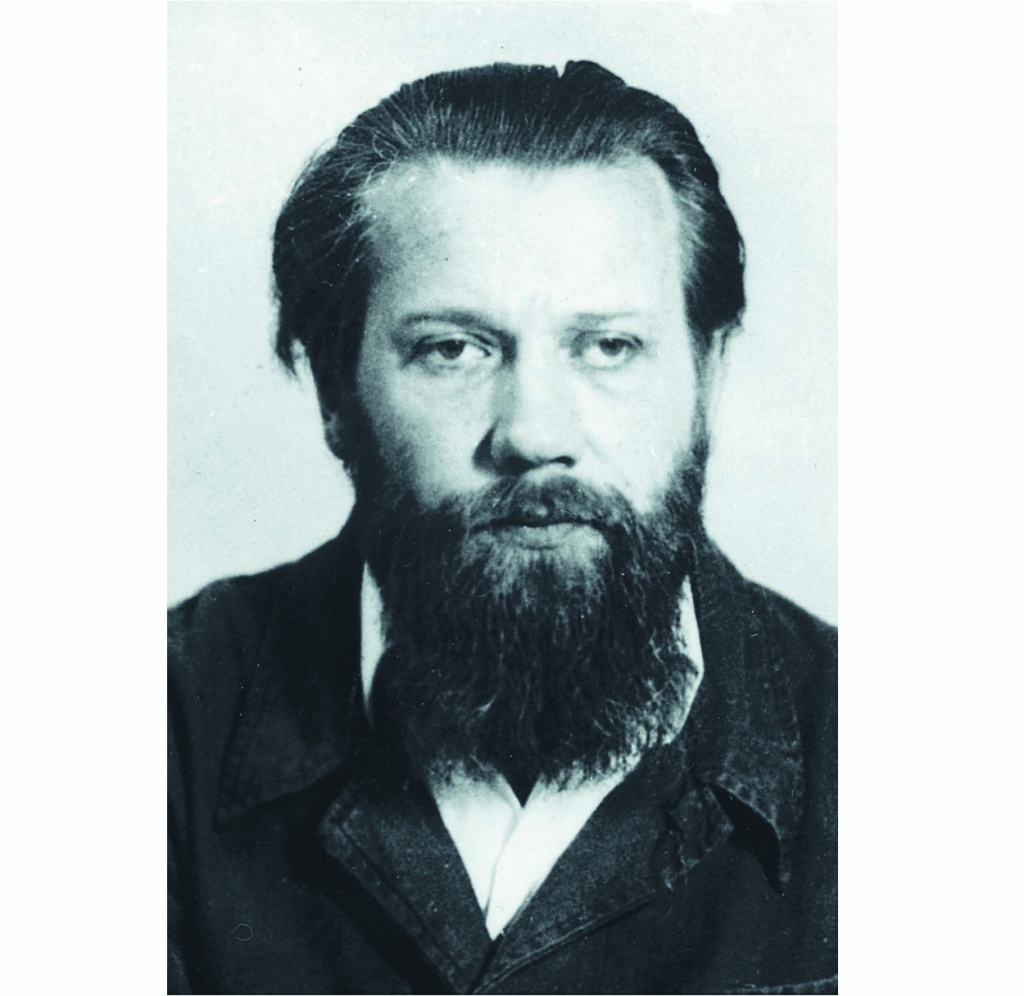

Andrei Sinyavsky

Andrei Sinyavsky, who some of you might know under the name of Abram Tertz, is a prolific Russian writer and literary critic. He has published some of his works in the West due to their… stylistic differences compared to the usual sort of literature permitted in the USSR.

The demonstration in support of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel

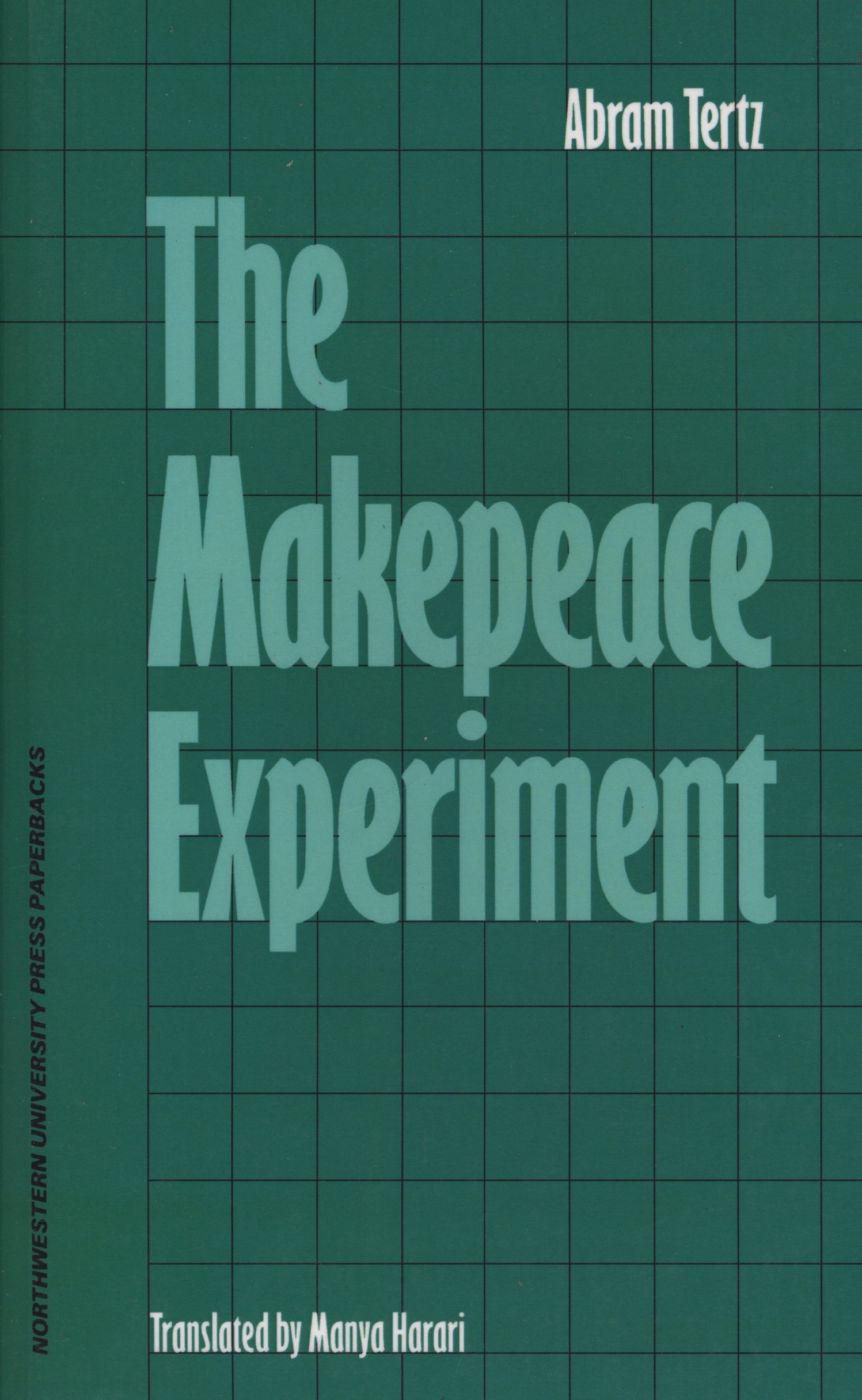

As such, I thought it would be appropriate to review one of his fantastical novellas.

Lyubimov or The Makepeace Experiment is an allegorical story about Leonid Tikhomirov (Lenny Makepeace) and a small town of Lyubimov. Lenny starts out as a simple bicycle repairman who falls in love with a new school teacher in town, Serafima. Serafima spurns his affection, saying he is too unambitious and unimportant for her. In despair, Lenny ransacks the local library, trying to find a way to improve himself, until he comes across an old tome containing the secret to mind control.

Yes, dear readers. Mind control. I was surprised, too.

Armed with that new power, he gains control over Lyubimov, forces Serafima to marry him, and attempts to create a veritable communist utopia in his town while cutting all ties to the USSR. Spoiler: he fails. And fails spectacularly.

So does the Soviet military while trying to retake the town, but at least that is expected in a story like this.

The novella, while absurdist, is also a political satire and commentary on human nature, rational versus irrational, and the dangers of the cult of personality. Unsurprisingly, it’s one of the reasons for the author’s arrest.

While the protagonist of Lyubimov is undoubtedly Lenny, the story is told to us by the town’s librarian (who becomes Lenny’s assistant) and commented upon by the librarian’s ancestor (a disembodied ghost who sometimes hijacks the narrative completely) through rather amusing footnotes. In the beginning the humor had me in stitches, even reminding me of Gogol sometimes. Sharp, cutting, and borderline sarcastic, it added richness to an otherwise not particularly compelling plot. Unfortunately, the farther in we got, the more jumbled the text itself became. It might have been on purpose, but it was hard to tell.

Still, the footnotes where the narrator argues with his ancestor about how to start the story or the scenes where Lenny makes the whole town see mineral water as pure alcohol or toothpaste as vobla paste were pretty funny. So was the way the Soviet military attempted to disguise itself to get into Lyubimov.

Vobla. For those of you who have no idea what vobla paste is.

It is a pity that most of the humor was lost in translation, as far as I could tell. The style of the original text was incredibly informal, almost folksy, which added to the absurdism of the whole mind controlled utopia situation, but I saw practically none of that in the translated version. That is not to say that the translation is bad, exactly. It is functional. However, it could be better.

The same could be said about the story itself. It could be better. As I said earlier, it started off well enough. But by the time the plot got to the middle of the book it was so meandering and vague it was hard to pay attention to the characters. The abundance of metaphors and allegories did not help matters.

The core ideas do still come through loud and clear, but I would have preferred them to be adorned in something I didn’t need to muddle through on the way over. By the end of the book I was actually looking to when I could turn the last page and finally say goodbye to it. It is certainly not something I would ever pick up on a whim to reread. Which is, again, a pity, since the first few chapters were incredibly enjoyable.

Another thing that made me grimace with disappointment was female characters. The novella has only three types: superstitious old women, harlots, or stupid peasants. Not the best combination at the best of times. Even Serafima, Lenny’s wife, is depicted as a harlot who our main hero is trying to mold into a respectable woman. Watching him get jealous over Serafima’s past lovers was not pleasant. Or, really, all that necessary to the plot or the characters’ development, now that I think about it.

That is not to say that the male characters are all the shining examples of intellect and nobility, but they are all somewhat sympathetic. The narrator is probably the only one that can be categorized as a good man. But at least the men are not cardboard cutouts of the worst stereotypes in literature.

So, to summarize. Does the book work as intended political satire? Yes. Do I recommend it to those interested in the subject? Yes. Do I recommend it to anyone just looking to have a good time? A definite no.

Additional warning for an extremely non consensual nature of the relationship between Lenny and Serafima which includes some very degrading and upsetting scenes. Mind control is not a healthy basis for a successful marriage; please remember that, folks.

I give Lyubimov a very generous two red stars.