by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

The House That Socialism Built

21 years ago this month, Winston Churchill gave his famous lecture “The Sinews of Peace” at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. Where he declared that:

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Atlantic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent…this is certainly not the Liberated Europe we fought to build up. Nor is it one which contains the essentials of the permanent peace.

The safety of the world requires a new unity in Europe, from which no nation should be permanently outcast.

Today Europe remains divided not just down the middle, but with the Northern states kept out of EEC, and right-wing dictatorships remaining in place on the Iberian Peninsula. However, so far warfare has remained largely absent from the continent and the debates within the Soviet Union do not seem all that different from those in Britain.

In the USSR, it has been announced 22 million people moved into new communal housing, but many of these higher paid workers are opting for new resident owned cooperatives instead. Whilst in England council house building has reached its highest level at 364,000, but that has been equalled by the boom in private housing.

Yet even with all this house building too many ordinary people have trouble getting a decent place to live. In Russia the necessity for putting up so many “Khrushchyovkas” is due to housing having been so poor for so long. In a survey in 1957, only 1% of the structures in Leningrad were given the highest rating by building inspectors, with more than half given the lowest. Whist in Kiev over 70% were given the lowest rating. In the UK the problem of the current housing crisis is perfectly illustrated by the harrowing recent film, Cathy Come Home.

Similar debates seem to be taking place in other areas, whether it is in as wages, healthcare and food prices. More and more it seems that sabre rattling and arguments over the best system of government are not dominating the headlines but, instead, how best to balance equality and pragmatism in the different economic systems.

With this alignment between the countries seemingly appearing, it is worth comparing two new anthologies, one from the UK and the other of writers from the USSR:

Carnell does not cite a theme for this collection, instead talking about breadth of ideas on display. For me, however, these all seem to be dealing with perspective and the nature of reality in some form. Unfortunately, these are not the best examples of this type of work.

The Imagination Trap by Colin Kapp

This is a sequel to Lambda One (which was also adapted for Out of the Unknown’s most recent season) where we get to see Bevis and Porter work on a new problem in Tau Research. Apparently not put off by the problems they encountered last time, a project is going ahead for “Deep Tau”, to use the same principle used to travel through inter atomic space within the Earth, to allow for a form of interstellar travel.

After last time, why would they agree to an almost suicidal trip into Deep Tau? On the Lambda II no less? Because of the titular 'imagination trap', which says that an expert in a field will always be compelled to follow a problem, no matter how dangerous to themselves. This kind of logic is the sort of thing which annoys me about this story, it continues to throw scientific mumbo-jumbo and ideas at you for almost 50 pages that don’t actually hold up to any scrutiny and expect you to go along with it.

My esteemed colleague Mr. Yon liked the original story significantly more than I did so there is clearly a market for what Colin Kapp is trying to do. But for me I will only give it two stars.

Apple by John Baxter

As a result of an unspecified war, all humans are now really tiny. Billings is a Moth Killer who goes into the tunnels inside an apple to slay the insect.

These kind of perspective stories have been with us throughout science fiction’s existence. From Voltaire’s Micromegas, through A. Bertram Chandler’s Giant Killer to Doctor Who: Planet of the Giants. And whilst this is very descriptive, I don’t see what this adds to the millions of other tales of this type.

Two Stars

Robot's Dozen by G. L. Lack

Unfortunately, G. L Lack continues to live up to their name with another disappointing story. In epistolary mode, we learn that Arthur Willis of Bath hires a robot duplicate of himself to watch his house whilst he is on holiday. The robot apparently takes to staring at the neighbours and so Arthur is forced to hire the robot again to prove it was not him. However, the robot rather insists on staying.

An obvious tale where the ending can be seen coming from the first paragraph.

Two Stars

Birth of a Butterfly by Joseph Green

For a century, humans have been exploring the galaxy trying to find intelligent life without success. However, it is a child travelling with his parents that discovers a unique form of intelligent life, small sentient stars that seem to resemble butterflies.

This could easily have been unreadable, but it ends up being a fascinating look at first contact with a totally alien form of intelligence and a rather sweet set of family dynamics. If nothing else, a definite relief after the first half of this anthology.

Four Stars

The Affluence of Edwin Lollard by Thomas M. Disch

Mr. Disch’s recent trip to England certainly seems to have been a success in terms of sales, for here is yet another tale from him appearing in a British publication. Unfortunately for us, this is not one of his best.

We follow the trial of the titular Edwin Lollard, who has fallen in love with the idea of poverty and a simple life of reading. However, in an affluent society obsessed with consumption this is hard to achieve and has to go to great lengths to try to get it.

This is the kind of dystopic satire I would expect to read a decade ago. You can see echoes of it in Brave New World, The Midas Plague, Fahrenheit 451 and a dozen similar works. The twist in the tale and courtroom proceedings aren’t bad but I cannot give it more than two stars.

A Taste for Dostoevsky by Brian W. Aldiss

Always a delight to see something new from Aldiss as, even if not successful, it will usually be different. This is a very strange type of time travel tale where someone seems to be jumping between different bodies throughout history or into alternative histories. Or possibly he is just an actor getting so involved in his roles he cannot determine the difference between fact or fiction?

This is certainly interesting, but I am also not sure what to make of it. Possibly if I was more a fan of Dostoevsky and familiar with the Freudian analysis of the texts that it seems to draw from I would possibly understand better what Aldiss was trying to say. Add into that that his attempts to explore ideas of race in it end up coming off as clumsy rather than profound, it ends up being a more middling tale to me.

Three Stars

Image of Destruction by John Rankine

Dag Fletcher first appeared in the opening two volumes of New Writings, but his subsequent adventures have been published in novel format. This picks up some time later in the series where Dag is now the chairman of Northern Hemisphere Corporation and is doing more work from behind a desk. The Interstellar Three-Four, captained by Neal Banister, is sent to Sabzius, a planet where the Commissar has recently disappeared. In order to oversee the situation, Dag heads to Sabzius with a skeleton crew.

This is 47 pages long, but it felt to me like 300. The prose was like wading through treacle and the story just kept dragging on. This could have been the kind of tense political thriller I enjoy but it didn’t go anywhere interesting and I failed to see any point to it.

I found the original stories dull and old fashioned so have not bought any of the continuing tales. This has not changed my opinion on this series.

One Star

So not such a good score from the capitalist society. Let’s see if the communist one can do any better:

Path into the Unknown: the best Soviet SF

The Conflict by Ilya Varshavsky

In a society where intelligent robots are employed as nannies, Martha feels threatened that her son Eric seems to prefer the robotic helper Cybella.

This is the kind of satirical vignette you would see as a space filler in F&SF. Add in that it is all layered with messages about a woman’s role and maternal instincts, and I found this to be a very poor start to the anthology.

One Star

Robby by Ilya Varshavsky

Another android tale from the same author. Here the narrator relates how he was given a self-teaching robot, Robby, on his fiftieth birthday, which he tries to use for household chores. However, it proves too literal minded for the tasks, cleaning shoes with jam if not given exact Cartesian coordinates or being unable to divide a cake into three because of recurring decimals. As Robby learns more about humans, he becomes increasingly difficult to live with.

This is a slightly longer story than the previous piece but no better. It is an incredibly simplistic machine logic narrative, more one I would expect in a children’s comic strip than as a piece of adult science fiction.

One Star

Meeting My Brother by Vitaly Krapivin

Three hundred years ago the Magellan photon space cruiser, captained by Alexandr Sneg, set off for another star system hoping to find an earth-like planet. They were never heard from again and assumed to be lost.

One of Alexandr’s descendants, Naal Sneg, is an orphan who sees the ship returning. With time only passing at one tenth the speed in cosmic space, Naal hopes to meet his ancestor and gain a brother he never had.

This is a slow meditative story, told in multiple parts, covering different facets of the tale to uncover the whole truth. I really liked it, if Robby feels like a story from a children’s comic, this feels like a strong novelette from Impulse.

Four stars

A Day of Wrath by Sever Gansovsky

A secluded laboratory developed a new kind of creature, the bear-like Otarks. They have a high degree of logic and intelligence but lack compassion, so will think nothing of attacking children, if the risk is not high, or just eating each other when hungry. Journalist Donald Belty is sent to investigate these creatures and to see whether they qualify as human.

This is an odd story. It is quite an engaging piece as it goes along but I struggle to understand quite what the point of it is. A criticism of unfeeling science, a satire on capitalism, or just a supposition extrapolated out? Whatever it is, the ending left me feeling quite uneasy and I am not sure if the author intended that or not.

A low three stars

An Emergency Case by Arkady Strugatsky & Boris Strugatsky

The Strugatsky Brothers will be familiar to long time journey readers as we have covered their material twice before. This is first of two tales dealing with alien life.

After dropping off supplies to Titan, Victor Borisovich discovers a fly on board their ship. Initially the crew are uninterested but when Malyshev, the ship’s biologist, recognises it has eight legs he realizes it is an undiscovered extra-terrestrial life form. Soon, though, the ship is overrun in these flies which seem to be resistant to insecticide. Can they contain or destroy them before the crew runs out of air?

Once you accept the unlikely life form they encounter, it is quite exciting monster science story that reminded me a bit of Vogt's Space Beagle tales. What lifted it up more is the excellent character work done, where each of the scientists has their own personality and are believable individuals in a small space of time.

A strong three stars

Wanderers and Travellers by Arkady Strugatsky

This is predominantly a conversational piece. Stanislav Ivanovich and his daughter Masha are marking Septapods, a type of freshwater cephalopod, with a supersonic tracking device to try understand their behaviours. They meet an astro-archaeologist, Leonid Andreevich, who tells them about the problem of “the Voice of Empty Space”, an impossible sound that is picked up by auto-wirelesses on space voyages.

I feel like there are some interesting ideas touched on here, but it doesn’t really go anywhere, except to suggest that the universe is perhaps illogical and unknowable. If that is the point, I believe it could be presented in more interesting ways than as a trialogue.

Two Stars

The Boy by G. Gor

A surprisingly intelligent schoolboy named Gromov writes the stories of the sole child on a long interstellar voyage. When these are read out to the class, all the other students highly entertained by them, but are they just fiction? Or do they have some connection to his father’s discoveries of alien artifacts.

This is an incredibly complicated piece of fiction involving narratives about narratives, theoretical physics, music, identity and perspective. And yet, it is also a story of friendship, where two lonely children form a bond. Really impressed with this and I hope more works from this author are translated soon.

Five stars

The Purple Mummy by Anatoly Dnepov

An interstellar signal has been decoded and used to reconstruct what appears to be the body of a woman albeit all in purple. The head of the Museum of Regional Studies in Leninisk comes to Moscow and shows the team holding the mummy that (apart from the colour) it is the mirror image of his wife. This appears to prove the theory that this signal came from a mirror universe of anti-matter, and it may also contain the secret of how to save his wife’s life.

As you might expect from the title, this reads like one of reprints from the Gernsback era you might find in Amazing or Famous these days. Even discarding how nonsensical it all is, no one’s reactions felt realistic to me and the plot with the illness is poorly handled.

One Star

Two systems, similar problems

Whilst this represents an overall win for Soviet architecture, in this case, both collections have their highs and lows, and there are definite areas for improvement. We will have to see if the next releases from either the UK or the USSR can build better structures.

![[March 18, 1967] From Both Sides of the Curtain (<i>New Writings in S-F 10</i> & <i>Path into the Unknown</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Banner.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

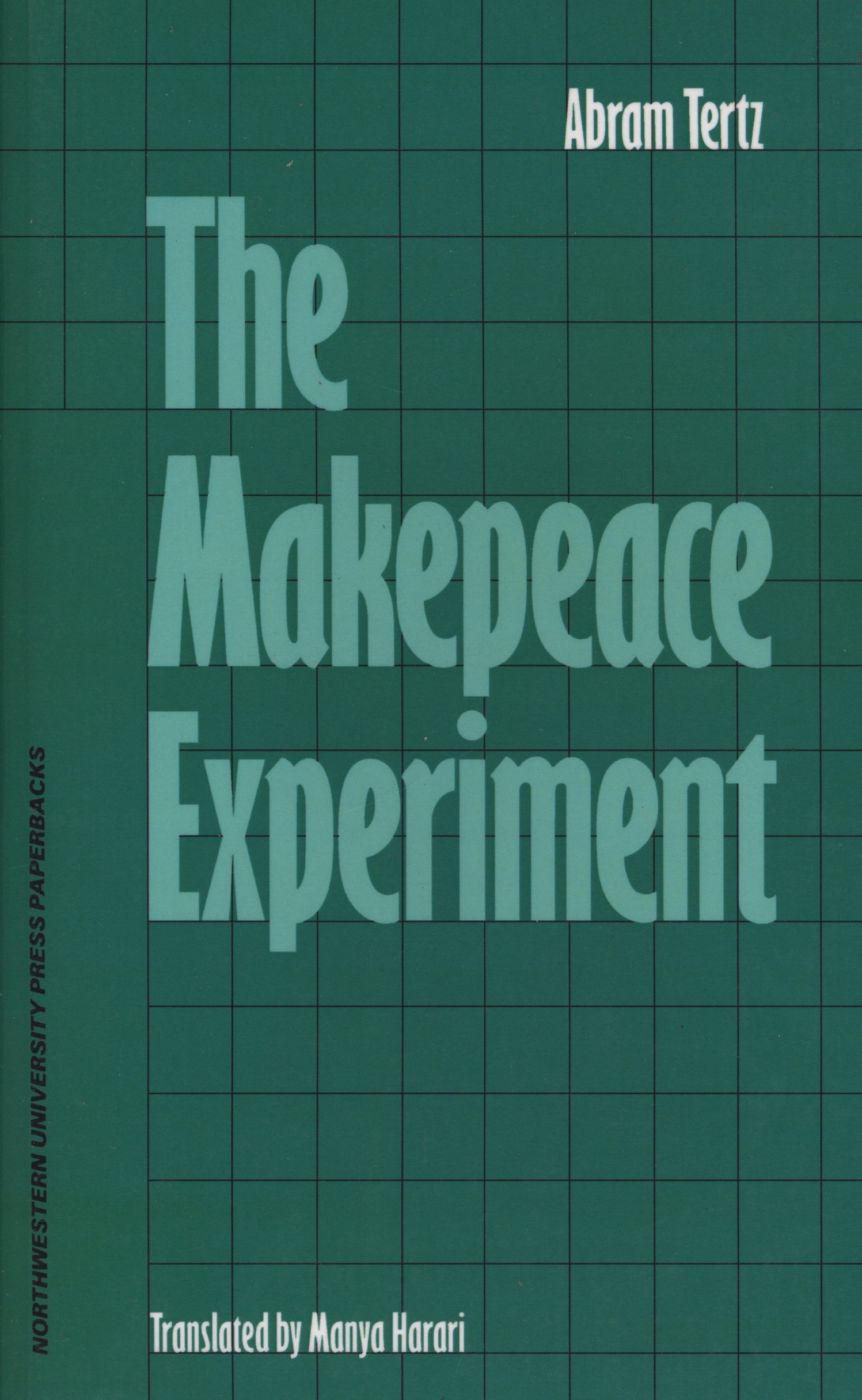

![[December 10, 1965] For the People, By the People <i>The Makepeace Experiment</i>, by Andrei Sinyavsky](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651218Makepeace-Experiment.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[September 4, 1964] (The Soviet novella, <i>From Beyond</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640904FO-3.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[Apr. 4, 1964] A taste of brine (the book and movie, <i>The Amphibian</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640403AM_1.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[November 11, 1963] An integral future (Yevgeny Zamyatin's <i>We</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631111cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[August 18, 1963] The Grass is Redder in the Future (Yefremov's <i>Andromeda: A Space Age Tale</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)