by John Boston

In all the excitement last month about August’s civil rights march, I forgot to mention the other big news that has reached from Washington all the way to small town Kentucky. On the first day of school, my home room teacher, sad expression on her face, informed the class that because of the Supreme Court’s decision, issued after the end of the last school year, barring official religious exercises in public schools

What a relief! But I kept a straight face and eyes front and was thankful that the authorities here decided just to obey the law. I gather in some places, mostly farther south, the peasants are out with torches and pitchforks. Anyway, one down. Fortunately, we only have to say the Pledge of Allegiance in assemblies every month or two, rather than every school day as is the case in some places. So it’s a relatively minor annoyance. What a blessing this modern Supreme Court has been. It makes all the right people angry.

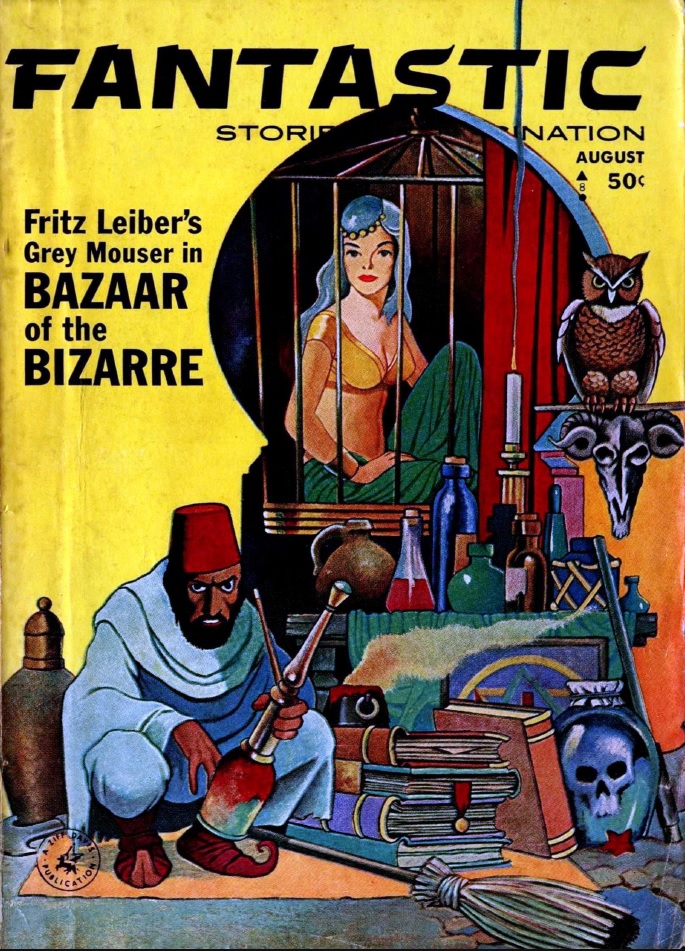

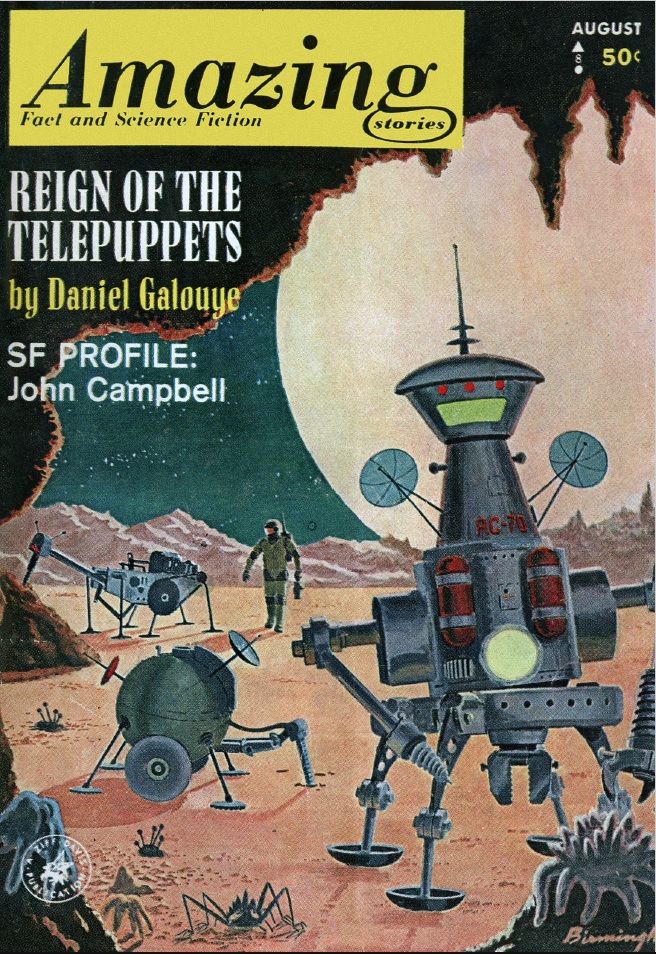

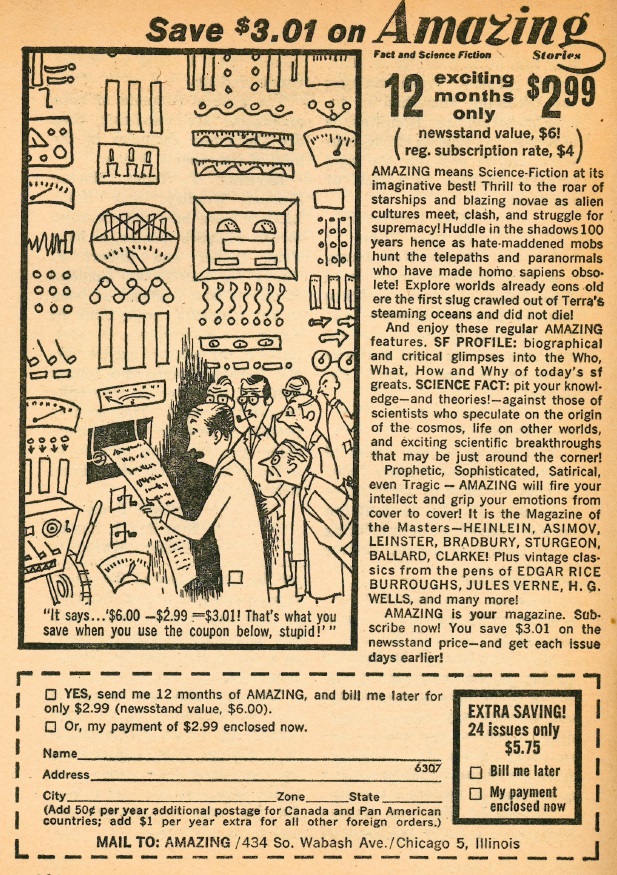

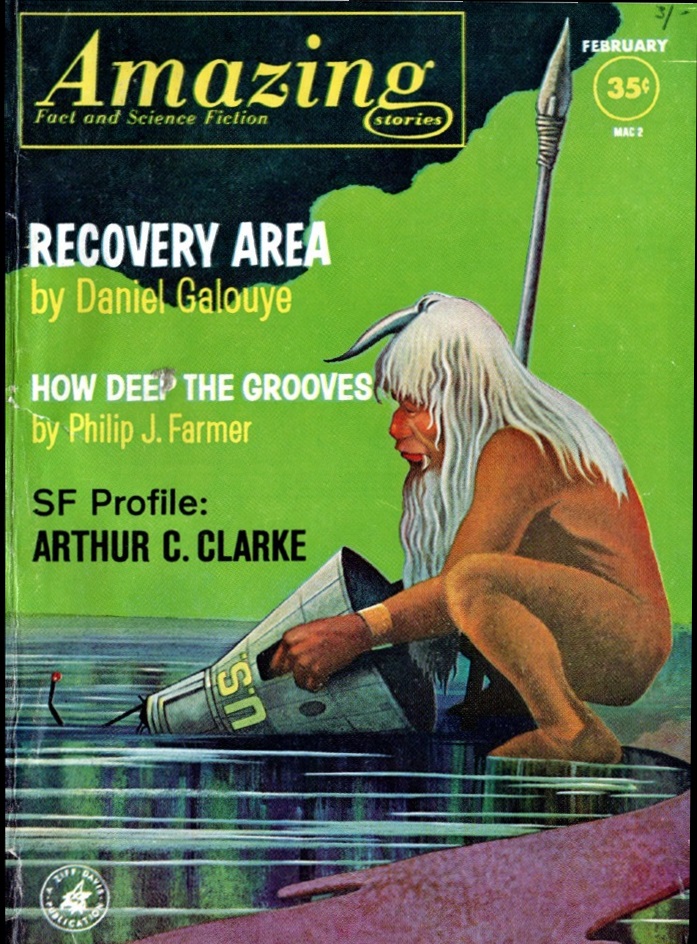

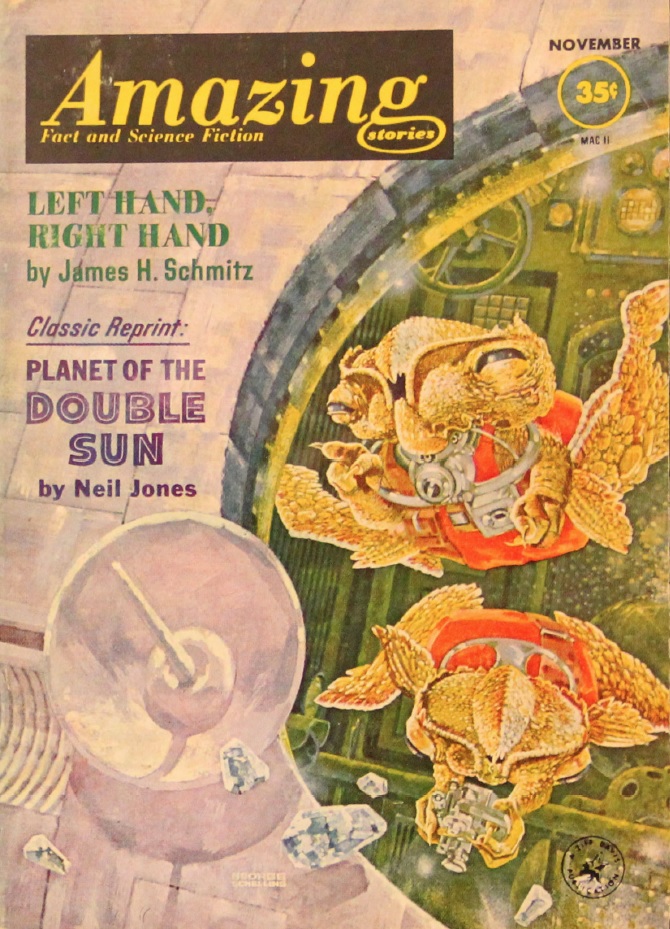

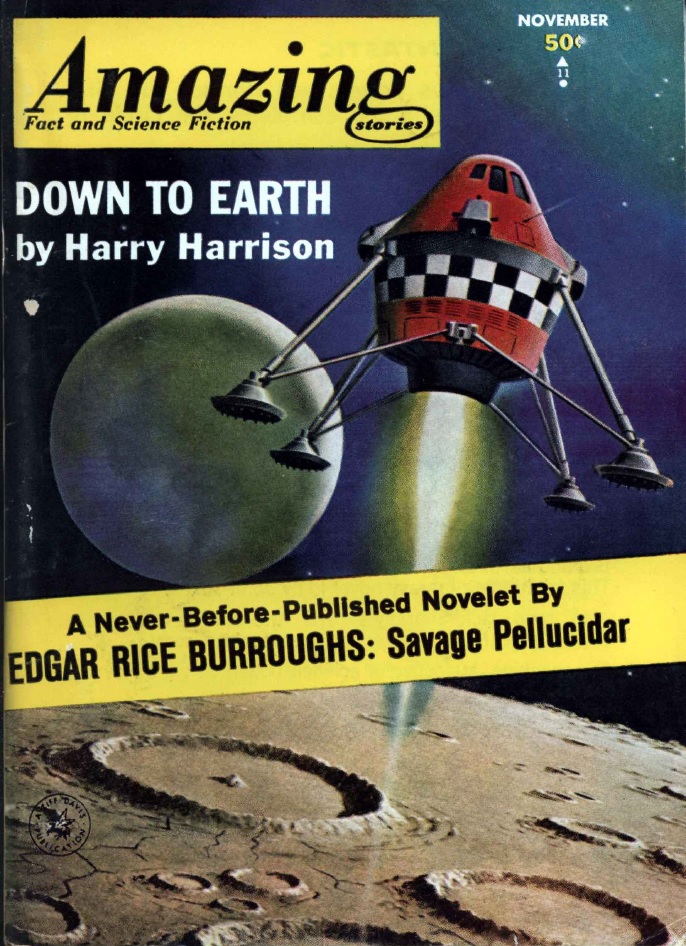

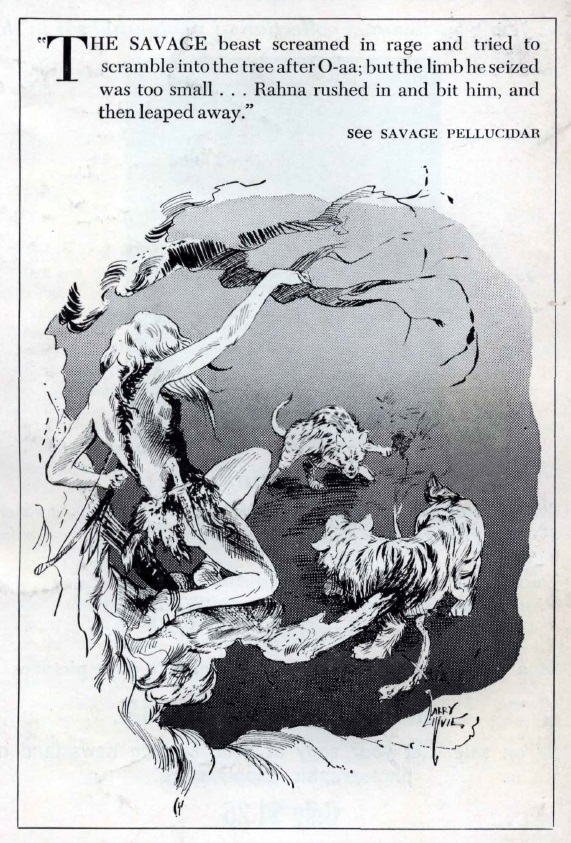

The November Amazing doesn’t make me angry, just bored, at least to begin. It is dominated by Savage Pellucidar, a long novelet by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the fourth and last in a series of which the first three appeared in Amazing in 1942. This one has been sitting in Burroughs’s safe for two decades, says Sam Moskowitz’s brief introduction. (ERB died in 1950.)

The story is set in Burroughs’s version of the hollow Earth, with land and oceans and a sun in the middle, in which various characters traverse the land- and sea-scapes mostly looking for each other, fending off several varieties of dangerous wildlife (reptilian and mammalian alike) and other perils, as the author cuts from plot line to plot line to maximize the suspense that can be wrung from this rather tired material. The obvious question: is why wasn’t this story published along with the others? One might guess that it was rejected—or perhaps Burroughs lacked the temerity even to submit it.

There is certainly evidence here that the author had grown a bit tired of the whole enterprise and had difficulty taking it seriously. One of the characters, a feisty young woman named O-aa, nearly falls to her death after escaping the fangs of a clutch of baby pterodactyls, saving herself by grabbing a vine: “ ‘Whe-e-oo!’ breathed O-aa.” Burroughs would have been pushing 70 when he wrote this. I gather his once impressive rate of production had slowed pretty drastically by the early 1940s. Maybe he was just too old and tired by then to produce even at his previous level of conviction, and had just enough discernment left to toss this in the safe and forget about it—unlike his heirs. One yawning star.

Or maybe I am just a cranky voice in the wilderness, or far out to sea. I see the Editorial celebrating the “astounding revitalization of Edgar Rice Burroughs,” and on the facing page a full-page ad for the new Canaveral Press editions of Burroughs—11 volumes published, eight more coming shortly, including one with the four Amazing novelets of which this one is the last. Catch the wave! Thanks but no thanks. Humbug for me, shaken not stirred.

So, what’s left to salvage here? There are three longish short stories, starting with Harry Harrison’s Down to Earth, which begins as an earnest near-space hardware opera, and continues with the astronauts returning from Moon orbit to an Earth—specifically, a Texas—in which the Nazis are in the end stages of conquering the world, though the beleaguered Americans quickly snatch the bewildered astronauts away from the invaders. A superannuated Albert Einstein appears, stealing the show and providing a solipsistic handwaving explanation. Matters speed to a predictably unpredicted conclusion. Most writers would have stretched this material at least to Ace Double length; Harrison crams it into a very fast-moving short story, and good for him. There’s nothing especially original here, but four stars for audacious presentation.

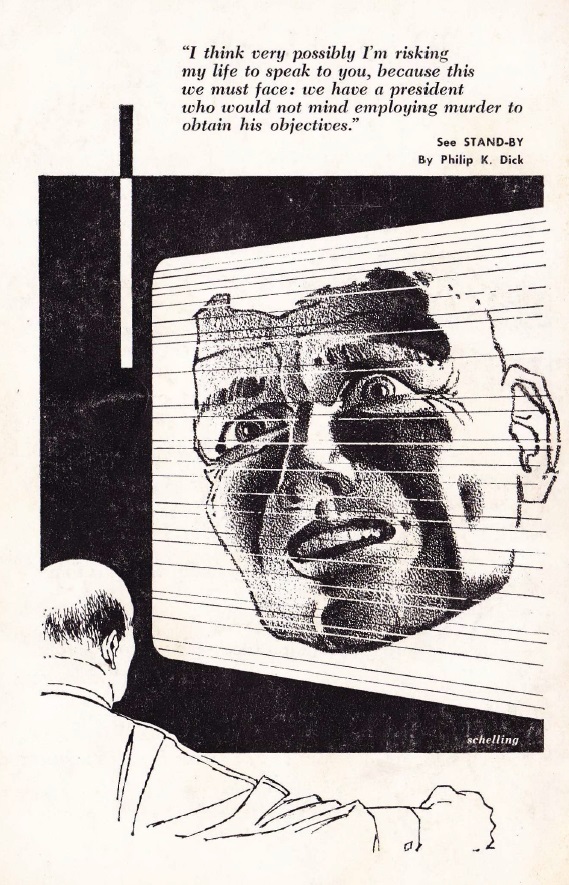

Philip K. Dick contributes his second story in two months, What'll We Do with Ragland Park?, which despite its title is not about urban planning, but is a sequel to last month’s Stand-By. Maximilian Fischer is still President, and he’s thrown the news clown Jim Briskin in jail. Communications magnate Sebastian Hada is scheming from his stronghold (“demesne” as the author calls it) near John Day, Oregon, to spring Briskin so Briskin can revitalize Hada’s failing network. To the same end, he recruits Ragland Park, a folksinger, whose songs tend to come true, and uses Park’s compositional talent for his own ends before realizing how dangerous it is.

There’s plenty else going on, such as Hada’s consultations with his psychoanalyst, Dr. Yasumi, who speaks in cliched semi-broken English (“Pretty sad that big-time operator like Mr. S. Hada falling apart under stress.”), and the unexplained fact that Hada has eight wives, one of whom is psychotic and is brought back from her residence on Io on 24 hours’ notice by the President to try to assassinate Hada. There are also things inexplicably not going on, like the alien invasion fleet which is mentioned in passing but doesn’t seem to be doing anything, or maybe the characters just don’t care. By any rational standard, this is a terrible story: loose, rambling, and arbitrary, in sharp contrast to Harrison’s tightly written and constructed story, or for that matter Dick’s own Hugo-winning The Man in the High Castle. But Dick’s woolly satirical ramblings are still clever and entertaining, like Stand-By more comparable to a stand-up routine than what we usually think of as a story. Three stars.

Almost-new author Piers Anthony—one prior story, in Fantastic a few months ago—is present with Quinquepedalian, which is just what it sounds like: a story about an extraterrestrial animal with five feet. Monumentally large animal, very large feet, with which it is trying to stomp the space-faring protagonist to death, not without reason. And it seems to be intelligent. How to communicate that it is pursuing a fellow sophont, and persuade it to let bygones be bygones? This one is for anyone who says there are no new ideas in SF, for certain values of “idea.” Four stars for ingenuity and a different kind of audacity than Harrison’s.

Ben Bova, whom I am beginning to think of as the 60-cycle hum of Amazing, has the obligatory science article, The Weather in Space, pointing out that the vacuum of space is no such thing; there’s matter there (though not much by our standards), plenty of energy at least this close to a star, plasma (i.e., ionized gas), the solar wind, solar flares, etc. This is accompanied by perhaps the most inapposite Virgil Finlay illustration yet for this series of articles. This piece is more interesting than most to my taste, or maybe just better suited to my degree of ignorance; I found it edifying, though Bova remains a moderately dull writer. Three stars.

Well, that was bracing. What’s the cliche? The night is darkest just before the dawn? Something like that, anyway. From the doldrums of ERB to three pretty decent short stories, in nothing flat and 130 pages. But I could do without the whiplash.

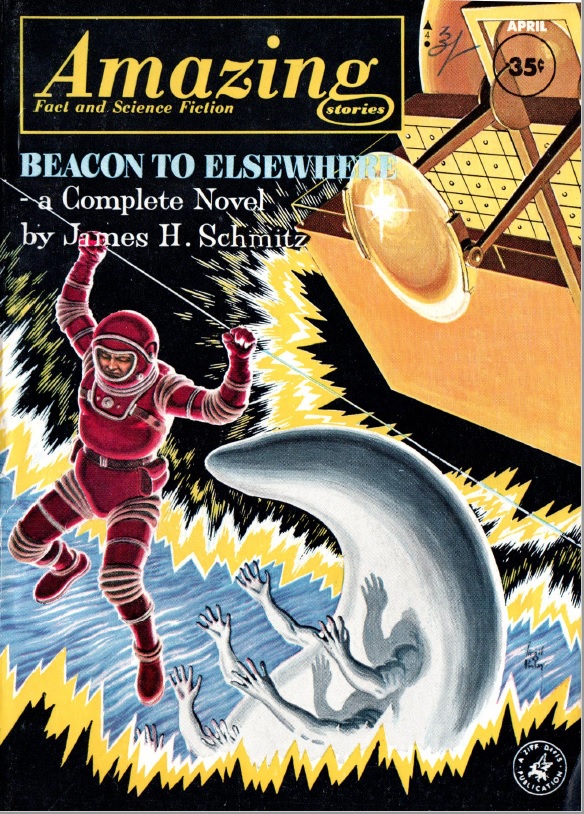

![[October 12, 1963] WHIPLASH (the November 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631012cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 13, 1963] COMING UP FOR AIR (the October 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](http://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630913cover-672x372.jpg)