A New Tradition

by Janice L. Newman

It’s official, we now have a “Star Trek” night at our house each week, when we gather our friends and watch the latest episode. Though we’ve only watched two episodes so far, the show is off to an interesting start! This week we saw “Charlie X”, which had thematic similarities to both of the pilots we saw at Tricon.

The Enterprise has picked up a refugee, seventeen-year-old Charlie, who is the only survivor of a colony that died years ago. He was found by another ship, Antares, whose crew is only too happy to be rid of him.

There’s immediately something fishy about the boy. This is emphasized by strong musical cues, which are nicely integrated into the score. Since I watched “The Cage” (the first pilot) only a couple of weeks ago, I wondered at first whether the Antares crew were actually aliens in disguise, or an illusion.

The boy is extremely awkward in his interactions. He’s fascinated by Yeoman Janice Rand, the first ‘girl’ he’s ever met, and follows Captain Kirk around like a lost puppy. No one seems to know quite what to do with him, and I felt bad for the kid at first.

However, strange things start happening aboard the ship, initially benign, or at least not damaging long-term. Charlie produces a ‘gift’ for Yeoman Rand and won’t say how he obtained it, even though she notes that there shouldn’t have been any in the ship’s stores. All of the synthetic meatloaf in the ship’s ovens are turned into cooked real turkey. Uhura temporarily loses her voice.

It’s clear to the viewer from the beginning that Charlie is making these strange things happen, but it’s not until he begins to take far more sinister actions that the crew become suspicious. The Antares attempts to contact the Enterprise at extreme range, saying that they need to warn them, but they’re cut off when their ship explodes without warning. Finally, Charlie makes a crewman disappear directly in front of Captain Kirk.

The entire story shifts at this point, and Charlie goes from being sympathetic to terrifying. He’s immature and impulsive, greedy and lonely. He’s got the power of a god and the conscience of a small child. He goes after Janice Rand, coming into her quarters and offering her a flower. She firmly and repeatedly tells him, “No,” but he continues to press his attentions on her until the Captain and Mr. Spock show up to help. When he casually tosses them aside, Yeoman Rand slaps him – so he makes her disappear, too.

There are echoes of “Where No Man” in this plot: a human obtains absolute power, which corrupts absolutely. It’s also reminiscent of the Twilight Zone episode, "It's a good life", which similarly features an omnipotent, frightening child. The ending to "Charlie", however, is unexpected. The aliens who gave Charlie the power in the first place, allowing him to survive in the lost colony, return to take him back. Charlie begs the humans to allow him to stay, saying he’ll be alone with aliens who cannot touch him and who cannot love.

This is an interesting turnabout; the audience is once again compelled to sympathize with Charlie. Despite all the terrible things he’s done, the viewer can’t help but feel sorry for the young man, trapped all alone with aliens. His situation is an interesting parallel to Vina’s in “The Cage”, but Vina stays behind by choice, and she is offered a rich fantasy life by the Talosians, whereas Charlie wants nothing more than to escape, and despite his powers, is apparently offered a sterile and empty life by his alien jailors. The nuanced story is far more sophisticated than typical television sci-fi fare.

However, there were a few elements that I felt rang false. Would Captain Kirk really be so awkward talking about ‘the birds and the bees’ with a teenager? Would Doctor McCoy really be so resistant to doing the same? This is the future, for heaven’s sake, and Doctor McCoy is a doctor. It felt like character and realism was sacrificed for cheap laughs.

On the other hand, I absolutely loved the way Charlie’s interactions with Yeoman Rand were handled. Charlie comes on strong and is increasingly pushy with Rand throughout the story. It’s a familiar kind of interaction in media. We often see a man persist in his attentions to a woman who resists at first but eventually gives in and falls in love with him. What made this story unusual was that his actions are never framed as being in any way romantic, or even acceptable. Rand is supported by the Captain himself, and never, ever told that she’s being hysterical or overreacting. When Charlie presses her, she stands firm, repeatedly telling him in no uncertain terms, “no!” and “get out of my room, I can’t make it any clearer than that!”

I appreciated how strong she was, and that Charlie’s actions were portrayed as creepy, unwanted, and wrong. It’s different from a lot of what I grew up with, and makes me wonder about the gender of the script writer, a mysterious “D.C. Fontana”.

Three stars.

A faltering step

by Gideon Marcus

Together with "The Man Trap", we are starting to get the first real understanding of the characters who inhabit the Enterprise. Dr. McCoy is back, marking the first time the ship's doctor role has been the same character. Moreover, he interacts substantially not only with Kirk, with whom he has a friendly, if perhaps arms length, relationship, but also Mr. Spock. Their bickering on the bridge presages what could be a fun running bit, where the science officer approaches things logically in contrast to the more emotional doctor.

On the other hand, Spock displays genuine emotion, both in his bashful smiles and irritation when performing with Lt. Uhura in the lounge (a nice scene — Nichelle Nichols has a lovely voice!), and also when playing chess with Captain Kirk and Charlie. This is the second episode that we have seen Spock and Kirk matching wits over the 3D version of the game of kings. I expect this is a motif we'll see more of.

While I enjoyed this outing, I found its execution more pedestrian than that of "The Man Trap". As fellow traveler Ginevra noted in our after-watch kibbitz, the use of camera pans, cuts, and focus are less adroit. The differently colored corridors we saw in "The Man Trap" have been replaced with ones of uniform reddish hue. It leaves the impression of a cheaper, less interesting show. Not to the degree of the second pilot (which will be aired next week), but it's definitely noticeable.

If I had to pick a stand-out scene, it is when Charlie zaps a crewman into oblivion, particularly Kirk's reaction thereto. You can see the character fitting all the pieces together about Charlie in stunning realization. I also appreciated Kirk's shyness in talking about women, and the relation of men thereto. He was established in the second pilot as "a stack of books with legs", and I appreciate a leading man who is not a ladies' man.

Perhaps that role will be taken up by Mr. Spock. Lord knows a certain communications officer seems to fancy him…

Three stars.

What makes Charlie X so frightening?

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

With last year’s founding of The Autism Society, many people are reconsidering the roles that disabled people can access in our shared world. Science fiction is an excellent place to stretch our imaginations and explore new worlds and futures.

In this week’s Star Trek episode, "Charlie X" Robert Walker plays the titular 17-year-old, progressing from awkwardness to outright violence; viewers moved with him from discomfort to horror to pathos. What made us react so strongly to Charlie? Charlie speaks too quickly or too slowly; interrupts Captain Kirk; stands too close; touches people in unexpected ways; has exaggerated expressions or a flat affect; makes uneven eye-contact; has sudden and overwhelming emotions he struggles to express in ways the crew can grok.

In the show, this is attributed to Charlie’s lack of socialization and education. But Charlie isn’t an illiterate boy; he’s a fictional character on TV, a representation of the actor, writer, director, and viewers' ideas of a monster, drawn from the shared fears of our society. The trouble is, not all of us fear the same monsters. In the world I live in, Charlie’s mannerisms reminded me of my family members who are autistic, who face violence from people taught to be afraid of them. Until he started hurting people, Charlie’s behaviors didn’t disturb me, but I could tell the actor and writer wanted them to.

This disconnect is what made the end of the episode so satisfying to me. My heart began to race in the final scene when first Lieutenant Uhura, then Captain Kirk, then the re-materialized Yeoman Rand pushed back against the Thasian leader. Fought to protect Charlie. Captain Kirk’s line, “The boy belongs with his own kind,” felt profound.

As readers know, the 1964 Civil Rights Act did not include protections for disabled people. In the future, perhaps another law will. Watching shows like Star Trek requires us to flex the same science fictional muscles that activists use to imagine new ways for our real world to be. Perhaps, to viewers in the future, Charlie’s mannerisms won’t evoke horror, but will be just one more way of being one of our own kind.

Three stars.

Of Gods and Magic

When it comes to Sci-Fi I am easy going on believability. Give me a simple (though sometimes far fetched) explanation for how or why something works and I’ll play along. But I am a stickler when it comes to “magic” (in Clarke's sense of the word). If I don't know how it works, I at least want to know its extent and cost.

My biggest problem with the episode is that Charlie’s powers are never defined in either category. Charlie is seen doing everything from procuring an object from thin air, to aging a character within seconds. Many of his abilities appear to be unrelated, yet exceptionally unlimited.

I almost wish Charlie’s powers had been to manipulate perception, like the alien in “The Cage.” This would have explained the variety of tricks Charlie executes during the episode: silencing Uhara, making crew members disappear – none of these things are really gone, just no longer perceivable under Charlie’s illusion. Even the change of beef to turkey could have been a simple trick of the senses.

Then again, there is a cost to Charlie's use of his "magic." It is, of course, that Charlie can never relate to other humans, and as a result, is exiled to emotional prison, living out his days with the Thasians. And while this isn't the kind of "cost" I was describing above, it does make for a compelling — and ultimately unsatisfying — episode.

Does he deserve to be condemned? I am hesitant to convict a character like Charlie of such a fate. After all, I believe his corruption was not from his powers alone. He endured some fifteen years of solitude. It is obvious Charlie lacks the socialization he needed during his formative years. I think in different circumstances, Charlie could have been more empathic, more willing to learn cooperation and patience in exchange for the social interaction and praise he so clearly desires. I think under proper care he could have been rehabilitated. Rather than thrown onto a large ship of strangers, better had he been given one on one time with a professional who could teach him what to expect once reintroduced to society. The Enterprise could really use a ship's psychologist. Failing that, Bones should have taken on the job.

While I’m happy the solution wasn’t to kill Charlie off, as the conclusion has been for menaces in episodes prior, I felt that Charlie was unjustifiably written off. It makes me wonder, what is the point of this episode? Charlie shows no character development or revelations. The Captain and crew feel badly for Charlie, but will they learn from their missteps that led to the crisis in the first place? I think this idea was ripe with potential left unexplored.

Three stars.

The Silent Treatment

by Tam Phan (Secret Asian Man)

Between the strange glares, close-ups, and whining monologues, we have the smatterings of a story about an awkward teenager playing grab-ass on the starship Enterprise. Much like “Where No Man” we’re often left staring at the characters staring at other characters waiting for someone to say something. Anything. Silence can be powerful, but sometimes silence is just silence. If I had wanted to watch a silent film, I would have chosen something a little more exciting.

Charlie really had his eyes set on Yeoman Rand, which is understandable. Any man with a good pair of eyes would, but she made it abundantly clear early on that she wasn’t as interested in Charlie as he was in her. The episode made sure to portray his advances as juvenile and unwelcome, which is a refreshing take on the overly aggressive pursuer getting the girl cliché. I appreciate seeing the consequences when “no” isn’t taken seriously. Charlie had powers that allowed him to do as he pleased, but it just goes to show that power isn’t everything.

I can appreciate that there was a deeper story here, but it wasn’t very well executed. I might have been sympathetic if Charlie was more likeable, but he just wasn’t. Nobody made an effort to improve Charlie’s experience in this episode. Not even the writers.

Two stars

From the Young Traveler

by Lorelei Marcus

"Charlie X" had an interesting premise that didn't quite match its execution. Charlie is meant to be a boy who has been raised in a completely alien context, his only reference to humanity being records and memory tapes. Yet aboard the Enterprise, his alienness is manifested in, at most, a lack of maturity and recognition of social cues. The difference should have been far more severe.

I believe the two main elements of "Charlie X" could have been better served as two different stories. One would be about an alien-raised human learning to assimilate with humanity. The other about an adolescent with ESP and the problems he causes.

We essentially got the second story, which after the mismatched premise, I have to admit was executed fairly well. Three stars.

Space Fashion

by Erica Frank

Obviously the most powerful organization in the future depicted in Star Trek is the fashion union. Changing starship uniforms every few weeks takes a lot of political swing!

Kirk appears in three different types of uniform in this episode: his command outfit, which he wears on the bridge, a gold shirt that looks more like what the other officers are wearing, and an exercise outfit that consists of tight red pants and little else.

Kirk's very fashionable command jacket, which looks easy to remove. This seems to be an important trait for the captain.

When he goes to teach Charlie the basics of combat, Charlie wears a red gi top (which must be standard sports outfit, since it's got the Federation patch near the shoulder), and Kirk wears… well…

Sulu(?) and another man are battling behind them with some kind of padded pole weapons.

That's certainly an interesting choice. It almost makes up for this being the fourth episode (out of four) with dangerous psychic powers.

Things I didn't like about this episode: Destructive mental powers (again). The crew leaving a rescued teenager to wander around the ship unescorted. Not assigning the teenager a guide, mentor, or other assistant to adapt to life in human society.

The ending felt a bit rushed; I'd like to see the Enterprise (or some other ship) visit the area again, and volunteer someone to live wherever Charlie's stuck with the aliens. Let them give another human — an adult — the same powers, and see if that person can teach Charlie how to live among humans without resorting to murder when his whims are thwarted.

Things I did like: The musical interlude was lovely; I enjoyed Mister Spock's Vulcan instrument and Uhura's spontaneous singing. Also, Charlie was sympathetic: we could feel his confusion and understand his petulance. The story made sense, even if I sometimes wanted to throttle the captain for not assigning someone to pay attention to Charlie sooner. Also, I will forgive quite a few plot sins if it means I get to see half-naked men tumbling around the screen on prime-time television. 4 stars.

If you dig the latest shows, tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Nothing but the newest and best hits!

![[September 20, 1966] In the hands of an adolescent (<i>Star Trek</i>'s "Charlie X")](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660920a.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

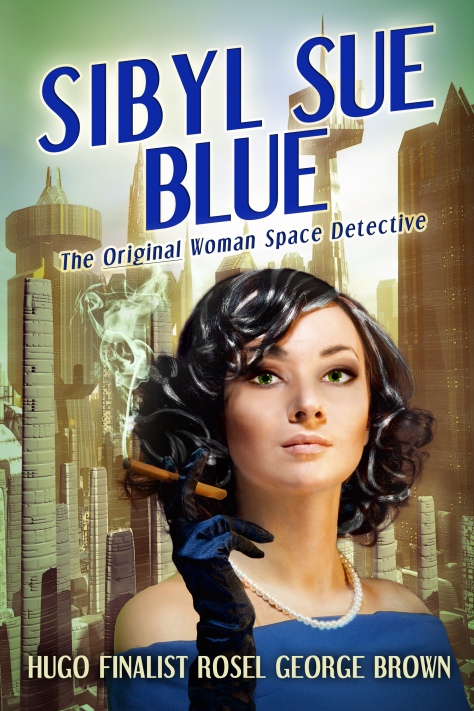

![[July 10, 1966] Froth, Fun, and Serious Social Commentary (<i>Sibyl Sue Blue</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Sibyl_Sue_1966.jpg?resize=452%2C372)

![[December 12, 1965] Something Old, something New (<i>The Bishop's Wife</i> and <i>A Charlie Brown Christmas</i>](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651212feature.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[February 15, 1964] Flaws in the seventh facet (<i>Seven Days in May</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640212may.png?resize=672%2C372)