by Jason Sacks

We here at the Journey pride ourselves on our international reach and viewpoint. We have writers from across the world, and we love to read work from a full spectrum of countries.

While we've dabbled a bit with Eastern European and Soviet fiction, this has been a bit of a blind spot for this zine.So when The Traveller asked me to review a new anthology of SF from behind the Iron Curtain, I jumped at the opportunity.

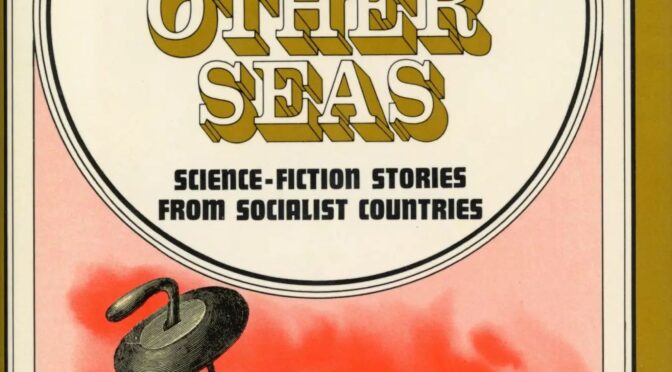

Other Worlds, Other Seas is a new anthology of science fiction stories from Socialist countries, published by prestige publisher Random House and edited by expert Darko Suvin. Suvin was born in the Yugoslav province of Croatia, and emigrated to Canada where he teaches at McGill University in Montreal.

Suvin still has deep ties to his native region, and has gained a reputation as one of the foremost critics and experts on SF from that area of the world. As part of that effort, Suvin has assembled a collection of fiction from some of the most prominent writers from that region.

As Suvin himself says, this is by design a quick overview. Other Worlds, Other Seas is only 200 pages long, so longer pieces were unavailable, as were stories from countries like East Germany for various reasons.

What Suvin compiled here is a classic mixed bag of stories. A handful of tales here are brilliant, a handful feel pointless. Allow me to break down that roster below.

The Patrol, by Stanislaw Lem (Poland)

All four of Lem's stories in this volume are parables in one way or another for the repressive and bureaucratic Polish state. None of his stories have the mysterious, allegorial power nor the mournful beauty of his masterful novel Solaris (1961). But all four stories are powerfully and cleverly written, and feel very much of our time.

We start with the tale of one Pilot Pirks, a pilot forced to fly into space alone for the most bureaucratic of reasons – as the narrator tells us, "although there was no need even for a single patrol rocketship, it was decided that there shouldn't be a 'hole' in the stellar maps, so the patrol flights began again with single rocketships."

Mysteriously, two other pilots had disappeared during their solo missions. Pirks soon finds out why, as a weird space anomaly seems to be teasing the ship as it wanders through space… but what is that strange object?

Lem adroitly depicts the loneliness of the solo space traveler and the slow descent of madness those travelers experience. This all feels like a parable of arbitrary missions and the meaninglessness of life under the Communist regime. I think it's the strongest of Lem's stories here.

4 stars

The Computer That Fought a Dragon, by Stanislaw Lem (Poland)

The tale of King Poleander Partobon, who is obsessed with cybernetics. But his love for cybernetics proves to be more than he can manage, as the machines run wild until the king takes action to stop them.

A parable about technology and hubris, and how that hubris can bring humbleness. This one is a bit obscure for me, but the playful, fairytale like style made this story a delightful read.

3 stars

The Thirteenth Journey of Ion Tichy, by Stanislaw Lem (Poland)

This section concludes with two sections from a story-cycle Lem created which satirize Polish politics. "The Thirteenth Voyage" is all about arbitrary roles and punishments, as our titular spaceman journeys into space to meet the brilliant Master Oh, wisest being in the galaxy.

As the spaceman travels, obsessed with his studies of philosophy (to aid in his understanding of Master Oh), he wanders off course, to a planet called the Piscatory, which is partially covered with water. There he finds himself an unwilling participant in a bizarre political tug-of-war, barely comprehensible to him and with rules that are constantly changing.

This piece is also written in Lem's customary charming style, and the satire seems pretty spot on if not completely obvious. This is a piece many Americans can understand — and probably empathize with.

3 stars

The Twenty-Fourth Journey of Ion Tichy, by Stanislaw Lem (Poland)

Another parable, this time with our spaceman protagonist landing on a planet where everyone dresses and acts exactly the same, where jobs and even families are swapped each day, and even the concept of death no longer exists because identity is so completely nullified.

Another rather obvious, even over-apt, piece, but Lem carries this story off cleverly and does a smart thing by giving readers the reasons why the society evolved to destroy individualism. This is the kind of story everyone from Teddy Kennedy to Barry Goldwater could cheer.

3 stars

The Contact, by Vladimir Colin (Rumania)

This escalatic story starts with a sentence full of wonder: "Everything is strange here, so strange that my exploration seems never to exhaust the stock of surprises in this world which is so different and deceptive." And this story ends with a gasp of thrilled surprise. In between, Colin conjures a strange and impossible world and a journey in his spaceman's mind as he discovers the transcendent truth he's discovered.

I was compelled by the poetic energy of this story, as well as Colin's solid inventiveness. I might have to seek out more of his work.

5 stars

Vampire Ltd., by Josef Nesvadba (Czechosolovakia)

If "The Contact" was poetic, "Vampire Ltd" is solid and has an element of Harlan Ellison's social satire. An East European man finds himself hitchhiking on a British highway. He gets picked up by a man in a most unusual car, and as we watch his journey, we see why this story's title may not just be metaphorical…

Clever writing by Nesvadba, full of energy and clear social satire, works to help make this a clever take on a familiar subject. I actually chortled a bit by the end of this tale.

4 stars

Why Atlantis Sank, by Anton Donev (Bulgaria)

A short-short story (a mere 3½ pages) and another bit of too-obvious social satire about a king who denies reality and faces the dreadful impact of his denial.

2 stars

The Master Builder, by Genrikh Altov (U.S.S.R.)

"The Master Builder" is one of those stories with clever ideas which feel just slightly out of reach. It's the tale of how mankind can journey to Jupiter – not physically but psychically, embedded in spaceships that are guided by the focus of the smartest men in history.

Altov aspires to make a larger point here about emotional and intellectual transcendence in opposition to implacable natural forces – human aspiration versus the power of nature. But all of this is a little too subtle for me, and I wonder if the ideas were lost in translation a bit. I wanted to get more out of this tale than I actually did.

3 stars

The Founding of Civilization, by Romain Yarov (U.S.S.R.)

This was another fun, quick yarn, the story of a time-machine racing competition – see, the trick is to see who can most quickly travel furthest into the past and then back again – and the truly unexpected consequences that happen when one of the racers breaks the rules almost accidentally.

This is a smart take on the mistakes many of us can make in the heat of a moment, and on the way technology can have completely unexpected consequences. I also appreciated how this was a thoroughly different variation on the idea of time travel. The story's ending twist was predictable but also delightful.

4 stars

Lectures on Parapsychology, by Ilya Varshavsky (U.S.S.R.)

Varshavsky's piece here isn't a story as much as a speculative essay making the case for parapsychology to be considered a science, complete with a few small anecdotes to illustrate his point.

Frankly, I don't understand why editor Suvin includes this piece in the book. It's not a story, it doesn't add much to the themes he's including, and he could have included something more intriguing in its stead.

Frustratingly, Suvin does something similar with another selection, soon to come…

1 star

Biocurrents, Biocurrents, by Ilya Varshavsky (U.S.S.R.)

Maybe "Lectures on Parapsychology" was meant as slight satire, because the other two Varshavsky stories included here are humorous little anecdotes. "Biocurrents, Biocurrents" imagines a transplant of teeth gone terribly wrong.

This story is quick, and fun, but very inconsequential. If I squint hard I can see a parody of Soviet incompetence, but it's easy to see a Western writer taking these same ideas and spinning something equally satirical.

2 stars

SOMP, by Ilya Varshavsky (U.S.S.R.)

We're at a conference in this story, and the speaker is presenting a lecture about a new machine he's created. The lecture is called "A Machine for Protecting Fools", or maybe it's called "Protecting a Machine from Fools." Or maybe all the people in the audience are fools.

Ho hum, hey readers, the emperor has no clothes! Moving on…

1 star

The Noneatrins, by Ilya Varshavsky (U.S.S.R.)

Oh, but here, finally, is a winner of a story by Varshavsky. "The Noneatrins" is a bit of a puzzle story. A team of cosmonauts land on an alien planet, and begin discovery. After a time, they discover life on the planet — but it's life of a sort never before imagined. Creatures dubbed Noneatrins have transparent skin, eat no food, drink only water, and have a completely placid life. What are these things, how do they survive if they don't eat, and how do the scientists figure out what these beings actually do?

Throw in a clever ending and you get a pretty cool and special exploration of alien life. With this and "The Contact", we get two tales which deliver impossible alien existences, and these both are spectacular little pieces.

5 stars

A Debate on SF – Moscow 1965, by Nikolay Toman (U.S.S.R.)

I have no clue what this is. Editor Suvin tells us this piece is a satire on the conversations Russian SF writers have when they get together, but the whole thing went completely above my head.

No stars because I just didn't get it.

Interview with a Traffic Policeman, by Anatoliy Dneprov (U.S.S.R.)

Other Worlds, Other Seas wraps up with a trio of stories by Anatoliy Dneprov, and they get progressively better and more intriguing as we read on.

"Interview with a Traffic Policeman" is an anecdote about a traffic stop. The man who drove through the light has all kinds of excuses why he committed the crime. Eventually he reveals he sees the world upside-down, and umm, yeah. I said these stories get better.

This is the nadir of the three Dneprov pieces, a cute little trifle.

2 stars

The S*T*A*P*L*E Farm, by Anatoliy Dneprov (U.S.S.R.)

Then we get an intriguing little tale, cast as a kind of wistful remembrance, of a man who aimed to have his children live exactly the same life he did – completely blissful as young children, and increasingly corrupt and evil the older they get. Eventually adolescent farmwork and budding romance turns into betrayal and robbery.

There's a lot in this story about conformity and the average man, about individuality and intent and regrets. There's a lot of veiled satire here about how Soviet society repeats its errors over and over again, but the wistful tone of the story keeps it grounded in true human emotion.

3 stars

The Island of the Crabs, by Anatoliy Dneprov (U.S.S.R.)

But it's Dneprov's final story here that works well as the book's endcap. It's perhaps the most universal of all the stories here. It's not hard to imagine a Western SF author writing this really cool piece. "The Island of the Crabs" is about two men sent to a small island to conduct research into the perfect weapon. As it turns out, that perfect weapon is a mechanical crab that eats metal. And as the crabs eat, they mutate and get larger and hungrier, and eventually threaten to destroy all metal in the world.

A reader can easily read this as a thrilling, high-energy tale of maun's hubris gone mad, or as a metaphor for Mutually Assured Destruction and man's ultimate self-destructive nature. Either way, this is a page-turner of a story that had me rapt.

5 stars

Conclusion

I think it's inevitable to feel slightly disappointed at the end of a survey like this one. When finishing a quick overview, a reader is often left looking for more depth – a deeper dive on an author, a set of additional books to seek out at a library, a list of writers to avoid.

That's how I feel, finishing Other Worlds, Other Seas. I enjoyed many of the stories Darko Suvin shared with me, and hanker to dive deeper into this unexpected and complex region.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!] Follow  on BlueSky

on BlueSky

Rachel S. Cordasco and I also enjoyed "The Contact."

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2024/04/14/short-story-review-vladimir-colins-the-contact-1966-trans-by-the-author-in-1970/