by Victoria Silverwolf

Wars Near and Far

The involvement of the United States in the conflict in Vietnam reached a turning point this month, with the signing of a joint resolution of Congress by President Lyndon Baines Johnson on August 10.

Doesn't look like much, for a piece of paper sending the nation into an undeclared war.

In response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident of August 2, when three North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the United States destroyer Maddox, the resolution grants broad powers to the President to use military force in the region. All members of Congress except Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon, Senator Ernest Gruening of Alaska, and Representative Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., of New York voted for the resolution. (Morse and Gruening voted against it, while Powell only voted present during roll call. Perhaps that was a wise move on his part.)

The name of the Navy vessel involved in the battle reminds me of the tragic domestic conflict in the USA over racial segregation. That's because restaurant owner and unsuccessful political candidate Lester Maddox shut down his Pickrick diner rather than obey a judicial order to integrate it. Let's hope this is the last we ever hear from this fellow.

This is a recently released recording of a news conference he gave in July defending his refusal to serve black customers. Please don't buy it.

The Battle of the Bands

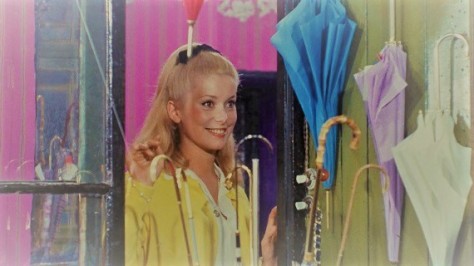

With all that going on, it's a relief to turn to less violent forms of combat. After withdrawing from the top of the American popular music charts for a couple of months, the Beatles launched an all-out assault with the release of their first feature film, an amusing romp called A Hard Day's Night.

Wilfrid Brambell is very funny in the role of Paul's grandfather.

Of course, the title song shot up to Number One.

I should have known better than to think we'd seen the last of these guys.

Not to be outdone, crooner Dean Martin, no fan of rock 'n' roll, drove back the British invaders with a new version of the 1947 ballad Everybody Loves Somebody, proving that teenagers aren't the only ones buying records these days by replacing the Fab Four at the top.

The Hit Version; as opposed to the forgotten version he sang on the radio in 1948.

His victory was short-lived, however, as a three-woman army entered the fray. Just a few days ago, The Supremes replaced him with their Motown hit Where Did Our Love Go?

I assume he does not refer to Dean Martin.

Order of Battle

The stories in the latest issue of Fantastic feature all kinds of warfare, both literal and metaphoric.

Cover art by Robert Adragna

Planet of Change, by J. T. McIntosh

Interior illustrations also by Adragna

We begin our military theme with a courtroom drama, in the tradition of The Caine Mutiny. This time, of course, the court-martial involves the star-faring members of an all-male Space Navy rather than sailors.

Before the story begins, the crew of a starship refused to land on a particular planet, despite the direct orders of the captain. This seems reasonable, as previous expeditions to the mysterious world disappeared. The mutineers obeyed their commander in all other ways.

During the trial of the second-in-command, who subtly persuaded the others to rebel, the prosecuting attorney investigates the defendant's background. It turns out that records about his past life and service record were conveniently destroyed. Under questioning, the strange truth about the planet comes out.

At this point, I thought the officer was going to be exposed as a shape-shifting alien in human form. I have to give McIntosh credit for coming up with something more original. The secret of the planet is a very strange one. Without giving too much away, let's just say that previous voyages to the place didn't really vanish.

Because the story takes place almost entirely at the trial, much of it is taken up by a long flashback narrated by the defendant. This has a distancing effect, which makes the imaginative plot a little less effective. The motive of the second-in-command, and others like him, may seem peculiar, even distasteful. As if the author knew this, he has the prosecutor react in the same way. Overall, it's worth reading once, but I doubt it will ever be regarded as a classic.

Three stars.

Beyond the Line, by William F. Temple

Illustrated by Virgil Finlay

A war can take place inside one's self also. The main character in this sentimental tale is a woman who is well aware that her asymmetrical face and body are unattractive. After a childhood spent escaping into fairy tales, and later writing her own, she decides to face the harsh truth of reality. Just as she does so, however, a rose appears out of nowhere in her lonely bedroom. It is asymmetrical also, and fades more quickly than a normal flower.

So far this reads like a romantic fantasy, but the explanation for the rose involves concepts from science fiction. Some readers may find it too much of a tearjerker, but I enjoyed it. It reminded me, in some ways, of Robert F. Young and his reworking of old stories, mixed with his emotional love stories. It's very well written, and is likely to pull a few heartstrings.

Four stars.

Fire Sale, by Laurence M. Janifer

Back to the world of armies and soldiers in this variation on one of the oldest themes in fantasy literature. The Devil appears to an important American officer. His Soviet counterpart is willing to sacrifice a large number of his own people to Satan, in exchange for killing the American. The Devil asks the officer if he can come up with a better offer. The solution to the dilemma is a grim one, which could only happen in this modern age.

This mordant little fable gets right to the point, without excess verbiage. You may be a little tired of this kind of story, but it accomplishes what it sets out to do.

Three stars.

When the Idols Walked (Part 2 of 2), by John Jakes

Illustrated by Emsh

It would be tedious to repeat the previous adventures of the mighty barbarian Brak, as related in last issue. The magazine has to take up four pages in its synopsis of Part One. Suffice to say that he faces the wrath of an evil sorceress and the invading army following her. The story eventually builds up to a full scale war between the Bad Guys and the Good Guys, but first our hero has to survive other deadly challenges.

In our last episode, as the narrator of an old-time serial might say, Brak wound up in an underground crematorium, from which nobody has ever returned. In a manner that involves a great deal of good luck, he finds a way out, leading to a rushing river. Next comes an encounter that could be edited out without changing the plot. Brak fights a three-headed avian monster, whose heads grow back as soon as they are chopped off. As you can see, this is stolen directly from Greek myth, and the author even calls the creature a bird-hydra.

Once he escapes from the beast, he finds the city of the Good Guys under attack from without, by the war machines of the Bad Guys, as well as from within, by the giant walking statue controlled by the sorceress. A heck of a lot of fighting and bloodshed follow, until Brak gets to the mechanical controls operating another giant statue, as foreshadowed in Part One.

Jake can certainly write vividly, and the action never stops for a second. The story is really just one damned thing after another, and certain things that showed up in the first part never come back. What happened to the strangling ghost? Whatever became of the magician who fought the sorceress? This short novel is never boring, but derivative and loosely plotted.

Two stars.

A Vision of the King, by David R. Bunch

Like many stories from a unique writer, this grim tale is difficult to describe. In brief, the narrator watches a figure approach with three dark boats. They talk, and the narrator refuses to go with him. As far as I can tell, it's about death, one of the author's favorite themes. It's not a pleasant thing to read, but I can't deny that the style has a certain power.

Two stars.

Hear and Obey, by Jack Sharkey

Illustrated by George Schelling

War can be waged with words instead of weapons, of course. In this version of the familiar tale of a genie granting wishes, a man purchases Aladdin's lamp from one of those weird little shops that show up in fantasy fiction so often. The genie takes everything the fellow says literally. (It reminds me of the old Lenny Bruce joke about the guy who says to the genie "Make me a malted.")

After a lot of frustrated conversation, the man finally gets a million dollars in cash. Since we have to have a twist ending, the fellow says something that the genie takes literally, with bad results. The tone of the story changes suddenly from light comedy to gruesome horror, which is disconcerting.

Two stars.

2064, or Thereabouts, by Darryl R. Groupe

Let me put on my deerstalker hat and do a little detective work here. Take a look at the author's name. Remind you of anything? Well, there's a first name starting with D, the middle initial R, and a last name that is almost like group, which means a collection of objects, just like the word bunch.

Even before reading the story, we can guess that this is David R. Bunch again, under a different name to weakly disguise his second appearance. Once we get started on it, the style and theme are unmistakable.

The setting is a dystopian future full of people whose bodies have been almost entirely replaced by machines. An artist visits, eager to do a portrait of the most extreme example of the new form of humanity, with only the absolute minimum of flesh left. Their encounter leads to a grim ending.

The plot is less coherent than I've made it sound. Like the other story by Bunch in this issue, it holds a certain eerie fascination for the reader, even as it confuses and disturbs.

Two stars.

Mopping Up the Battlefield

With the exception of a single good story, this was yet another issue full of mediocrity and disappointment. Maybe I'm just in a bad mood because of the looming threat of global warfare abroad, and a new civil war at home. I should probably relax and watch a little television to get my mind off it, even if I have to put up with those lousy commercials.

![[August 25, 1964] Combat Zones (September 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FANTSEP1964-e1565757244659.jpg?resize=427%2C372)

![[July 20, 1964] Dashed Hopes (August 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/26179.jpg?resize=400%2C372)

![[June 22, 1964] The Bridal Path (July 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640622cover.jpg?resize=477%2C372)

![[June 16, 1964] Strangers in Strange Lands (August 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/6312017cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[June 8, 1964] Be Prepared! (July 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640608cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[May 22, 1964] Not Fade Away (June 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640522cover.jpg?resize=507%2C372)

![[May 18, 1964] Aspirations (June 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640518cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

tiny piece in which we learn:

tiny piece in which we learn:

![[April 20, 1964] Play Ball! (June 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640420cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[February 21, 1964] For the fans (March 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219cover.jpg?resize=665%2C372)

![[January 22, 1964] The British Are Coming! The Americans Are Here! (February 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640122cover.jpg?resize=513%2C372)