by John Boston

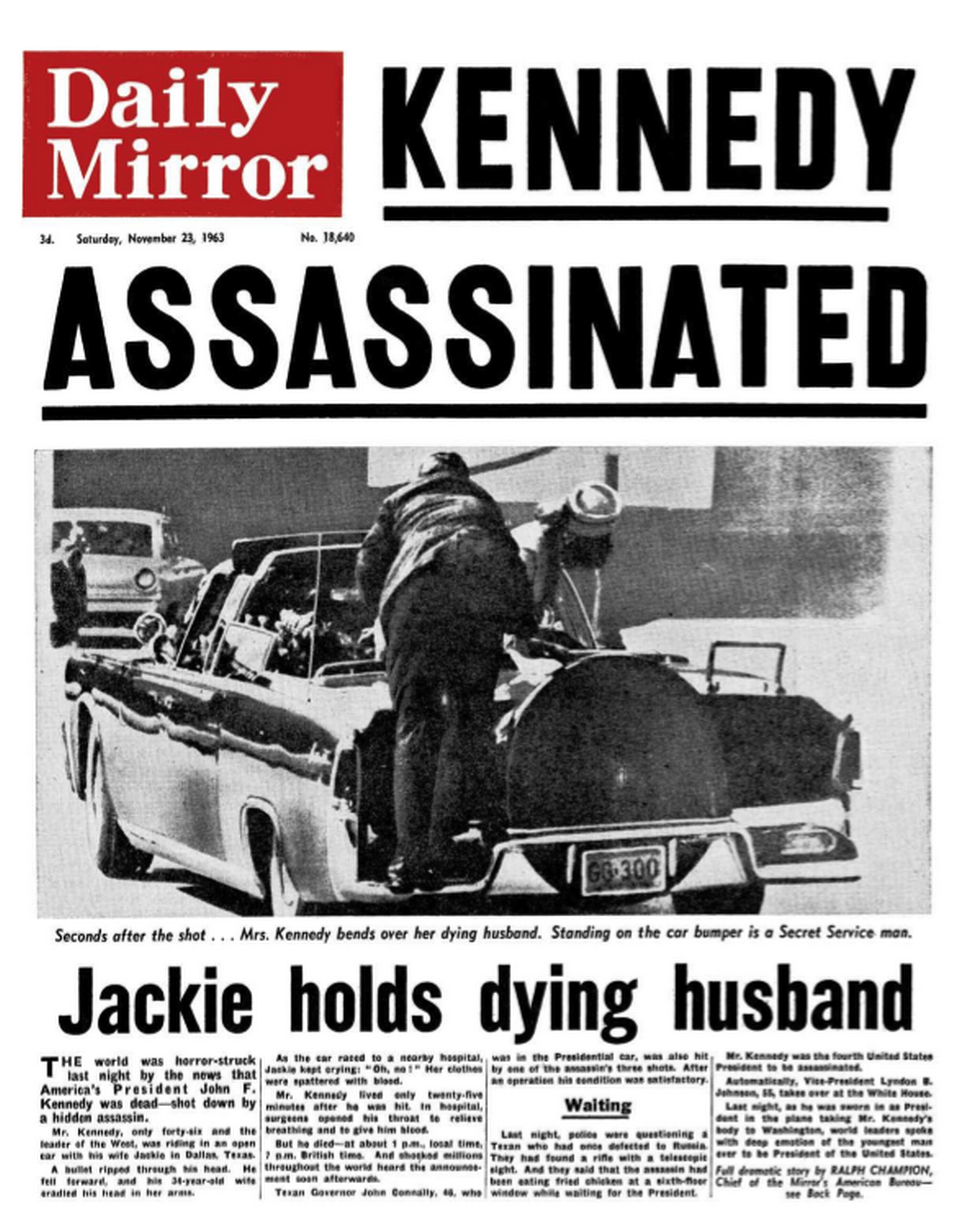

The shock of President Kennedy’s assassination remains new and raw in the public consciousness and public discourse, but there are starting to be some discordant notes. Malcolm X, one of the leaders of the Nation of Islam—the Black Muslims in common parlance—who seems to have appointed himself as the skunk at America’s picnic, was asked about the assassination a couple of weeks ago and described it as a case of “chickens coming home to roost,” which he said “never did make me sad; they've always made me glad.”

Apparently he meant to suggest that the assassination had some relationship to our government’s actions around the world—and of course he is not the only one to make this connection, though it remains to be investigated. Needless to say he was roundly condemned by everyone in sight, including his own organization, which censured him and barred him from public speaking for three months.

Oh, well. In Malcolm’s absence, we have the January Amazing to chew on. Not surprisingly, given this magazine’s manic-depressive history, it is gristlier and less nutritious than last month’s unusually tasty issue.

Speed-Up!, by Christopher Anvil

When a writer seems to have a lock on a high-paying market and suddenly appears in a low-paying one, one of two things has happened: it’s a pretty bad story, or it has hit one of the higher-paying editor’s blind spots. Or maybe both. Christopher Anvil has had 21 stories in the SF mags since January 1960, all but three in Analog. Yet here he is in Amazing, where he’s never appeared before, with Speed-Up! (exclamation point his, or the editor’s).

This is a story which juggles multiple elements of dubious plausibility, including not one but two psi talents, and only manages to integrate them by blowing the whole thing up, as the cover illustration suggests. And one of those elements is a movement that thinks science is too dangerous and should be stopped—and is proven right! On the other hand, it is a pleasant enough read, unlike some of Anvil’s Analog stories: tightly constrained exercises within the confines of editorial expectations, which create a reading experience reminiscent of anoxia. Two stars.

The Happiness Rock, by Albert Teichner

Albert R. Teichner’s The Happiness Rock is an annoying morality tale of the oh-so-conventional kind, anoxia compounded by anesthesia. Officer Cramer and Captain Hartley are exploring the asteroids and, landing on one, find silicon dust that makes people happy upon inhalation, without noticeable impairment or physical addiction. It proves to be a silicon microorganism, but the silicon seems to be quickly metabolized with no lasting effects. The corrupt Captain keeps the discovery secret and shuts Cramer up, unknowingly abetted by their cartoon military martinet of a superior, who places Cramer in an unlikely status of Probation that keeps him silent, while the Captain takes the dust to his shady friends on Earth to help him covertly market it.

Cramer struggles to find a way to blow the whistle on this racket. Why? Because this seemingly harmless euphoria must exact some terrible price, just because, and of course it does, quite arbitrarily. The story goes on for 25 pages, most of them unnecessary: mediocre writing skills in the service of cliched thought. One star.

Skeleton Men of Jupiter, by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs is back (one is tempted to say “from the grave, again”) with Skeleton Men of Jupiter, from the February 1943 issue of Amazing, where it should have stayed. It is labelled a Classic Reprint, but is not decorated or burdened with the usual Sam Moskowitz introduction. It is another in the series about John Carter of Mars, or Barsoom, and opens with his being kidnapped by the cadaverous characters of the title.

Oh no. Not this again. I read some of the John Carter books a while back, and that seems to be the main plot motivator of Burroughs’s work: kidnappings and captures, followed by the obligatory escape and rescue efforts. The skeleton men are led, or served, by a red man of Mars, who explains that he is here because his aristocratic girlfriend Vaja was kidnapp…wait a minute. This is three pages after the first kidnapping. How many of these are we going to get in this fifty-plus-page story?

Slogging on: the red man of Mars, U Dan, tells his sad story of servitude in the cause of Vaja to a faction of Jovians, or Sasoomians in ERB’s cosmology, who of course are seeking world domination; they’ve got Sasoom and now they want Barsoom, and are they evil. U Dan says: “They are fiends. . . . when I learned that Vaja would be tortured and mutilated after Multis Par had had his way with her and even then not be allowed to die but kept for future torture, I weakened and gave in.”

Well, life is too short for this. Literarily speaking, we have moved from the realm of anoxia and anesthesia to that of morbidity and mortality. In the spirit of the season, bah humbug. One star and a pile of dust.

Interstellar Flight, by Ben Bova

Those three are the only fiction items in the magazine, anything else having been crowded out by fifty pages of Burroughs. There is another article by Ben Bova, Interstellar Flight, in which the usually slightly dull author gets positively giddy. The blurb warns us: “With factual tongue and a lot of imaginative cheek, our man Bova explores the possibility of [title].” And . . . oh no, he’s everywhere! The article begins with an imaginary TV show panel with an imaginary SF writer, who begins: “Edgar Rice Burroughs, writing some 50 years ago. . . .”

Averting my eyes briefly, I move on. SF writer says we must go to the stars, physicist says “Impossible!” and explains why, engineer and astronomer chime in with assorted factual constraints, mathematician gets into the act, and the problems of interstellar travel are laid out reasonably neatly. Then: “ ‘Excuse me,’ said the astronomer. ‘Have any of you ever heard of the Bussard Interstellar Ramjet?’ ”

Now that you mention it, no. It’s actually a pretty interesting idea for sublight but very fast travel: take just enough fuel to get moving fast enough (and build a scoop big enough) to take advantage of the clouds of hydrogen gas floating around most places in the galaxy, and use them as fuel for fusion; the faster you go, the more fuel you can gather, so the faster you can go. This doesn’t solve the problem of relativistic time dilation—but so what? Somebody will want to go, and maybe take the whole family! Most satisfyingly, Bova concludes: “Edgar Rice Burroughs, hah!”

Well, that was actually informative, and less dull than usual, though slightly marred by the absence of the customary completely inappropriate Virgil Finlay illustration . Three stars—the brightest spot in this otherwise bleak landscape.

Summing up

Feh.

Next month, the editor promises a novella by the capable and prolific John Brunner, who has not previously appeared in the magazine, and, one hopes, may provide enough publishable copy to keep away the shade of ERB.

![[December 13, 1963] SLOW-DOWN (the January 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631213cover.jpg?resize=456%2C372)

![[December 11, 1963] Count every star (1963's Galactic Stars)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631211stars.jpg?resize=527%2C372)

![[December 7, 1963] SF or Not SF? That Is the Question (<i>They came from mainstream</i>, 1963 edition)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631207apebook.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[December 5, 1963] A Composer After My Own Heart (A theme song for <i>Dr. Who</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631205delia_derbyshire.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[Dec. 3, 1963] Dr. Who? An Adventure In Space And Time](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631203hartnell.jpg?resize=600%2C372)

![[November 29, 1963] An old doll's new tricks (<i>Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 5-8)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631129c.png?resize=672%2C372)

![[November 27, 1963] … Death, Doctors and Mythology ( <i>New Worlds, November 1963</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631127cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[November 25, 1963] State of Shock (December 1963 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631125cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)